Stagflation could be a future scenario. The Federal Reserve and the government are printing limitless amounts of dollars to inject into the economy, and while that happens, the supply of goods and services is decreasing due to deglobalization.

Unemployment, inflation, and recession are realities not far from becoming ours, the first one has already started to grow exponentially.

But as frightening as this might sound, we can prepare and learn how to invest so we can continue to build wealth regardless of the circumstances.

In this article, I will compare today’s inflation with the 1970’s case, analyze the unemployment rate in the months to come, and look at the misery index.

After this overview, I'll share with you what investment strategies I’ve over time and why.

Let's Go Over Inflation And Stagflation

The Misery Index is set to explode, and I am going to explain how you should invest for it.

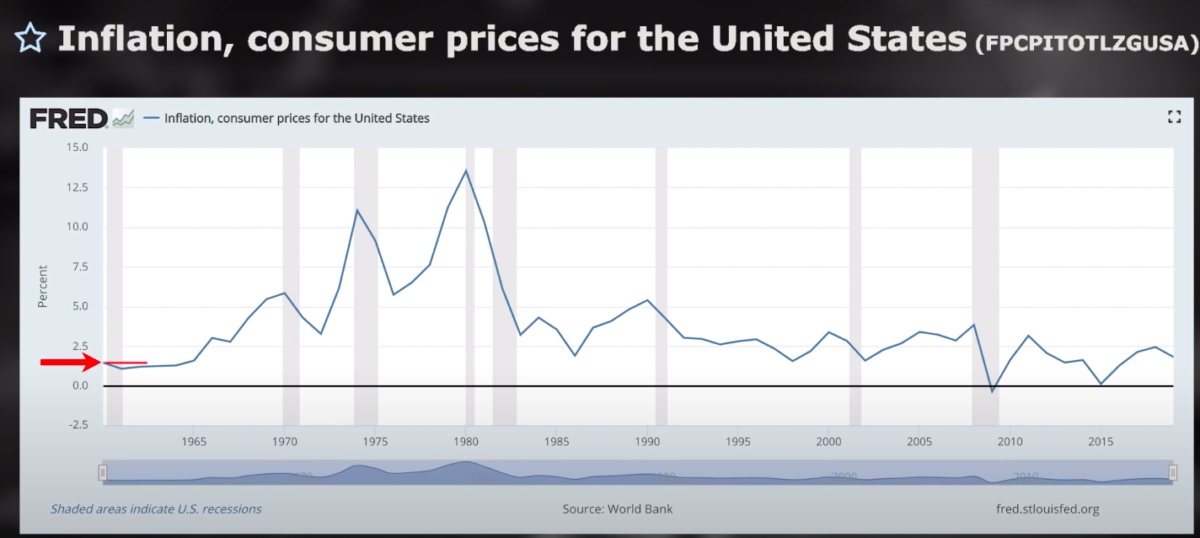

Let's begin by going over inflation and the last time we had stagflation, which was back in the '70s. Look a this chart.

It goes back to 1960 and vertically, it goes from 0% inflation, all the way up to 15%. It started off very low in 1960 and then started to creep up around 1970. It went back down in the early '70s, but then it shot back up as it got to a peak in 1980 at almost 15% inflation.

Keep in mind, that's 15% inflation that the government was willing to admit to, it was most likely a lot higher than that.

Volcker came in and destroyed inflation by jacking interest rates almost up to 20%. It came crashing down from 1980 to 1985 temporarily at about 5%. That's right when we had The Plaza Accord.

During this time, the dollar in the international markets, especially relative to the Yen in the Deutsche Mark, went down by 50%, but domestic inflation was only around 5% or 6%.

It went up slightly until 1990 when it came down. Later it went back up a little bit before the dot-com bust, then it peaked up in 2007, and came crashing down to a little less than zero.

Although we had massive asset deflation, the consumer price index barely got down below zero, and asset prices came crashing down by more than 50%.

That's the way the government measures it, which is most likely lower than reality.

In 2010 it went back up but came right back down in 2015. Then it leveled off to where we supposedly are today, based on the government numbers.

I also want to point out that from 2008 to 2012, home prices, which is most people's main asset, went down in value steadily. It bottomed out in 2012. While at the same time, the CPI, the prices of goods and services you buy on a daily basis went up.

It's very important we understand that asset prices can go down, while the cost of goods and services, the stuff you buy on a daily basis goes up.

How does this apply to what's going on today?

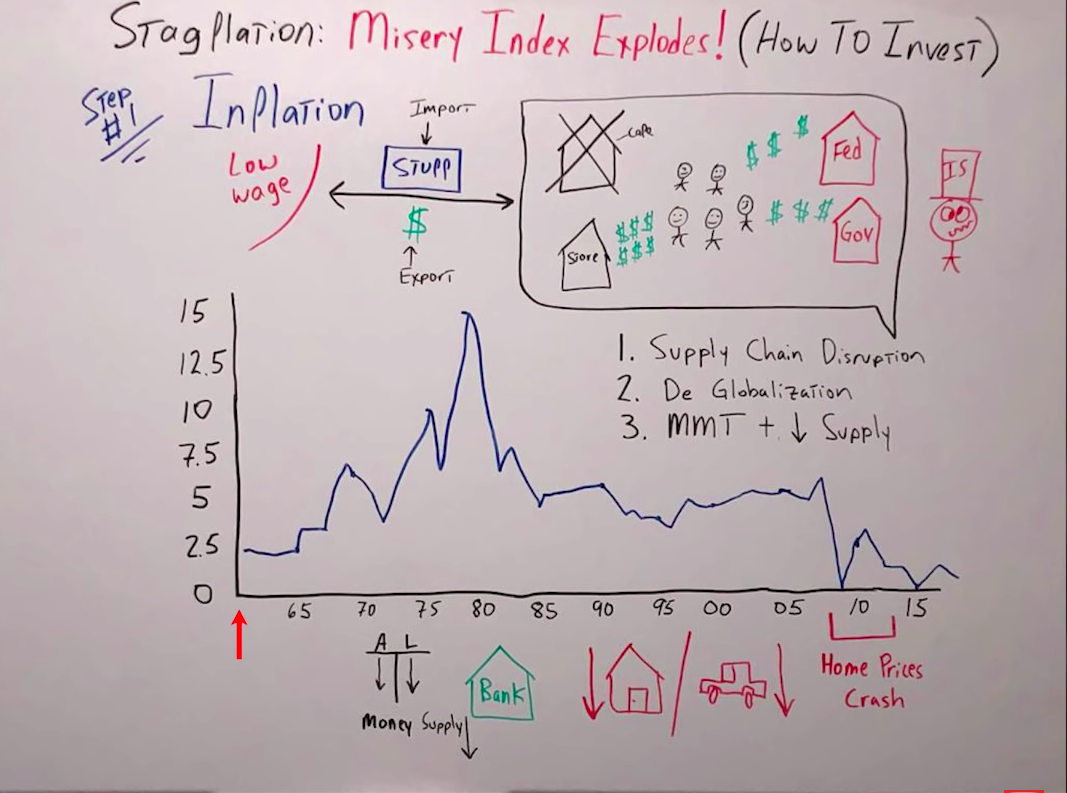

Here is the same chart but this time I drew it so I can explain myself better.

On this chart you can see my awesome map of the United States. Believe it or not, I drew that by myself, and on the right, we have your insolvent, most likely drunk uncle Sam.

The Fed and the government are printing up funny money like there's no tomorrow, and they're spending it into the economy, creating deposits most likely through MMT.

Of course, they're monetizing that debt because the Fed's buying it almost immediately to keep interest rates low, but the Fed is also creating deposits in the real economy because of all the four-letter and five-letter “solutions” they launched in March.

They're creating deposits. They're not just creating extra reserves held at the Fed for the primary dealers, and we have our grand total population in the United States of five people.

The Fed and government, between them, create $6 of additional money that goes right into the pocket of these five people, but unfortunately, they don't have many options for food.

They had the option of a cafe or a store, but the cafe is shut down due to the Coronavirus and might shut down permanently.

The only option is for them to take the $6 of MMT they received from either the fed or the government, and spend it at the store.

What happens if the supply decreases and the amount of money increases?

Of course, price inflation.

Unfortunately, it gets worse, because we now have supply chain disruptions and we're going to have a massive push in the future, in my opinion, towards deglobalization.

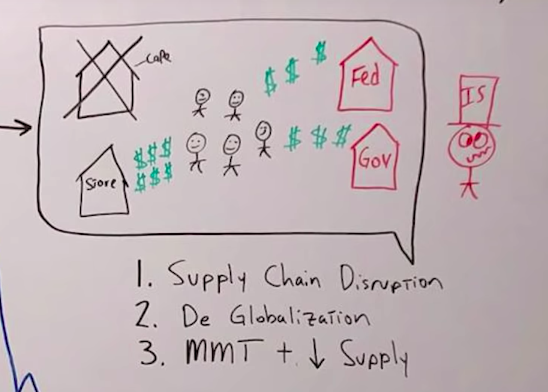

How does that work?

We have a low-wage country XYZ that would import stuff to us in the United States, and we would give them dollars for the stuff that they manufactured at a low price and sent to us.

Our imports were stuff and our exports were these green pieces of paper, called dollars.

Well, if the low-wage country is importing us fewer medical masks, pharmaceuticals, and we're creating more of the stuff here…

- Prices immediately go up, even if we could create those domestic supply chains, because we don't have low-wage workers.

We have high-wage workers, and the price of our inputs for all those goods and services immediately goes up, and that's if we could produce it in the United States.

- Additionally, we have more dollars staying in the United States circulating.

Before, when we would export dollars, let's say we had an additional $6 in the system. Well, two or three of those dollars would leave the United States and go to the low-wage country, so only $3 would be circulating in the U.S.

But, now we could face a scenario where all six of those dollars are circulating in the United States, creating more domestic consumer price inflation.

Why?

Because we're not exporting those dollars and we have a higher supply of money due to MMT, and a lower supply of goods and services.

The rebuttal is “George, yes, but because people aren't taking out loans, then that decreases the dollars in the system.” If you're thinking about thus you are absolutely right. You definitely watched my video with Brent Johnson, but let's think this through.

If we have a bank and their balance sheet has assets and liabilities, the liabilities are deposits, assets, loans. If they have fewer loans, the money supply is decreasing, but what are they creating those loans to buy?

Usually, it's something like a house or a car, there would be fewer dollars created, but the money supply is contracting for homes and cars, not necessarily food you buy at the grocery store.

See where I'm going with this?

We have a setup where the stuff you buy on a daily basis are going up in price, but the homes, cars and other assets, are going down.

I think it's very likely over the next year or two, we could see inflation that would be very consistent with what we saw in the 1970s. Above 6% going up to 10, maybe even 15%.

Let's Discuss Unemployment

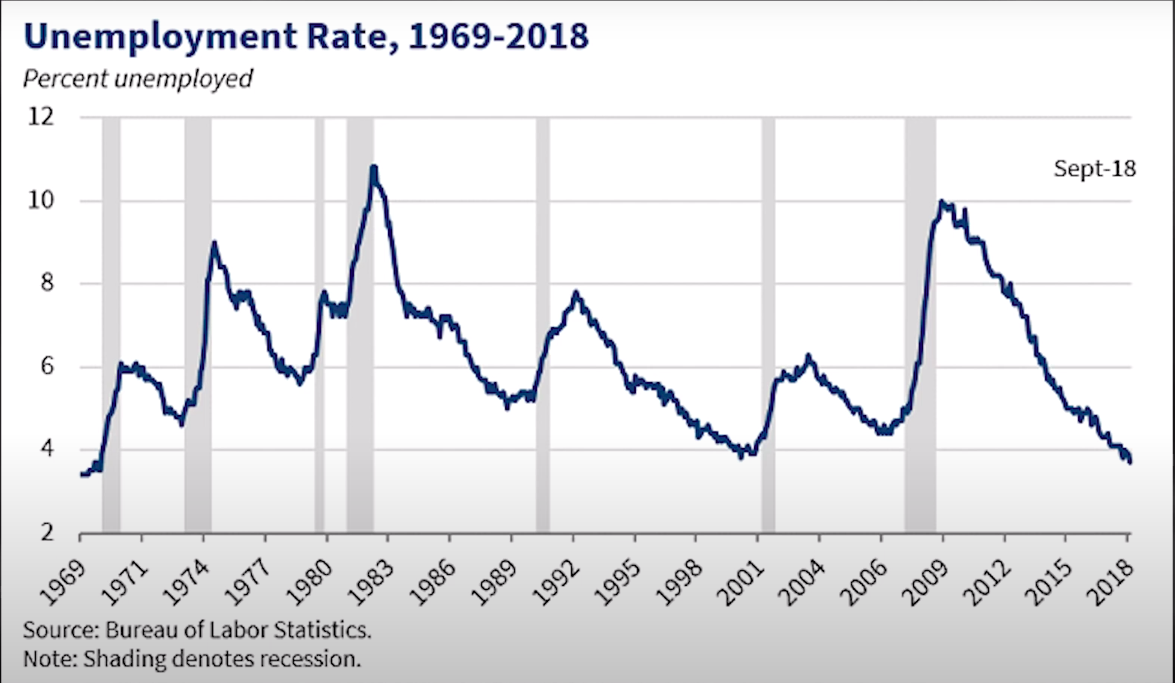

Here is a chart of the Unemployment rate going all the way back to 1970 until today.

On the left-hand side, the unemployment rate goes from zero, all the way up to 12%. We started 1970 right around five or 6%.

That went up in 1970 to almost 10% and came down a little bit, but then skyrocketed to over 12% in 1980 until 1982, then it came back down in 1985.

Things were getting pretty good in 1990, but then, it went back up to over 8% when we went through that mild recession of 1990. Unemployment gradually came all the way down until we got to the dot-com bust. We had another recession so it went up near 8% and came down before the GFC.

It raised up again to 12% and finally came all the way back down to where we were as of March of 2020. Where unemployment was at an all-time low.

At this point, coronavirus arrived. There are many analysts that believe the unemployment rate can go up to 30%, if not higher according to St Louis Fed's Bullard.

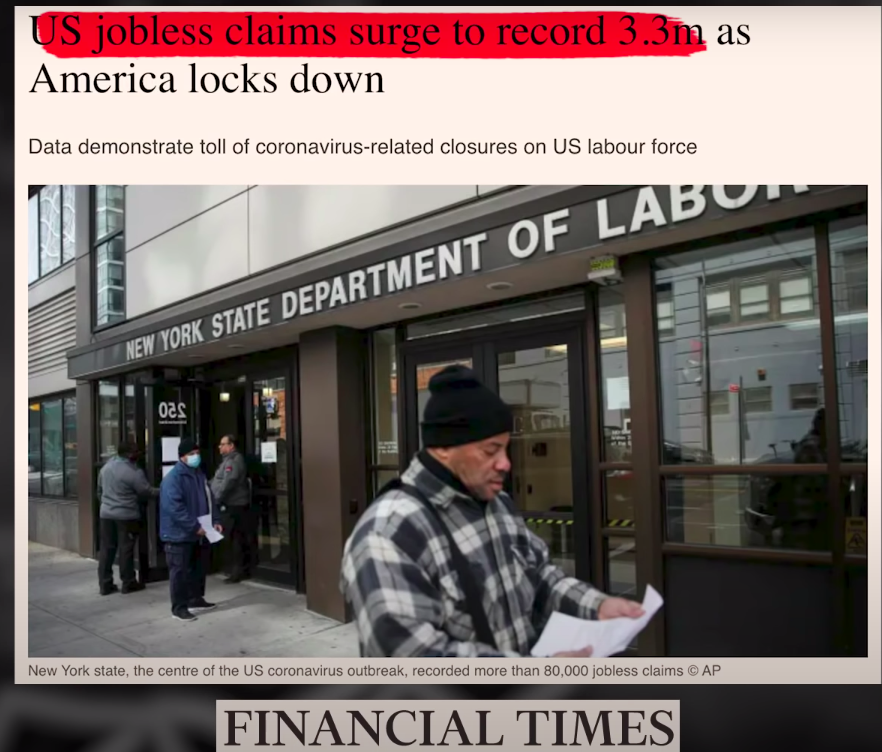

In March 26 of this year jobless claims were at 3.3 million, and it's not hard to understand how they're coming to those numbers.

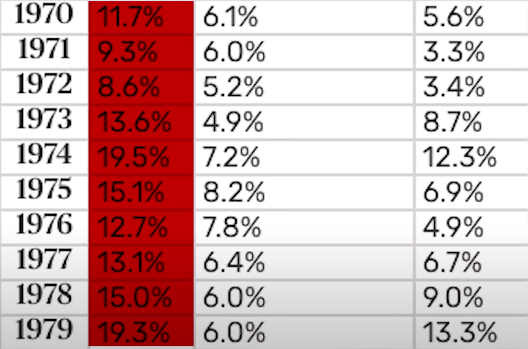

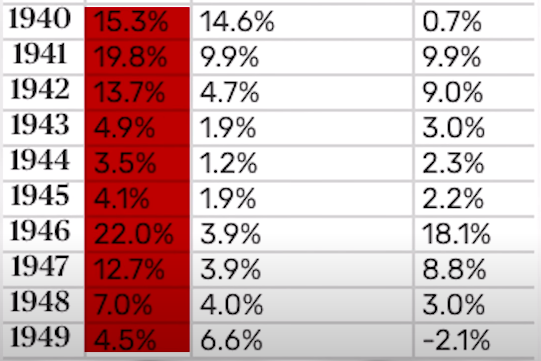

If we have inflation at over 10%, which I think is very realistic on the goods and services you buy on a day-to-day basis, and we have unemployment at 30%, where does that put us on the Misery Index?

Far higher than we were in the 1970s, the 1940s, during World War II when we had the interest rate peg or the yield curve peg that they're suggesting we do now, and it's far worse than what we had in the 1930s during The Great Depression.

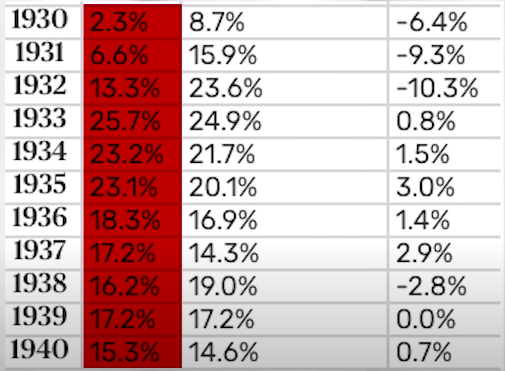

Look at the following sheets to see what I'm talking about.

Let's go over some potential solutions.

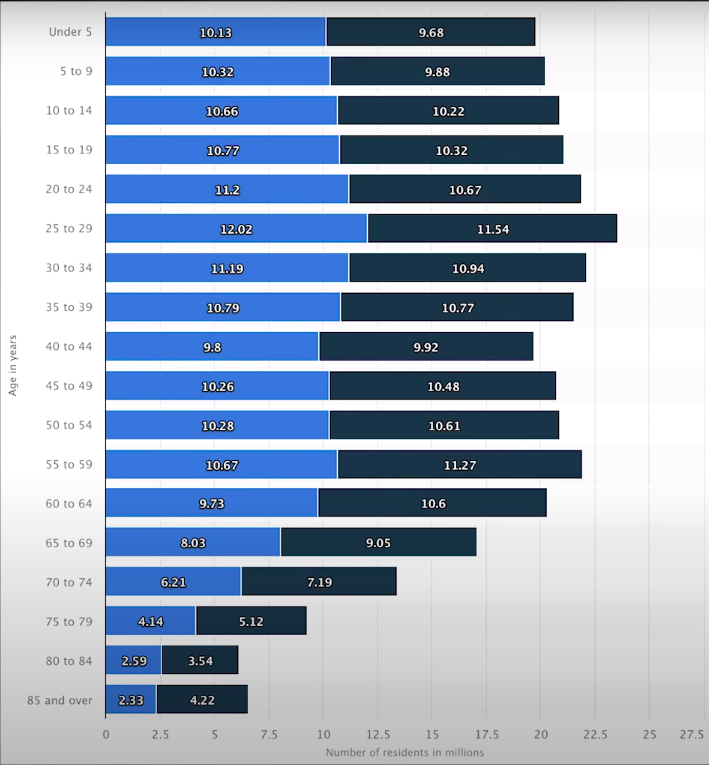

- One thing that's being talked about all the time is quarantining people who are most at risk.

Let's just say that you quarantined everyone over the age of 55. In the following chart, you can see that it would be about 60 or 65 million people.

I'd like to point out, those are the older people with the money. The young people don't have money to spend, so if one man's spending is another man's income, and I know that's kind of Keynesian, but to a certain degree, I think that's very true.

It all starts on the supply side but there is a demand component to this as well, especially when your economy is 70% consumption.

Since we can all agree, no matter how optimistic you are about the COVID-19, that the unemployment rate would skyrocket if 60 million people were quarantined in the United States.It still takes the unemployment rate at least as high as we had in the 1970s.

Now, let's talk about services.

Since that's such a large part of our economy, what happens when all the restaurants close? I've read headlines saying that 10 to 30% of the restaurants in the United States could go out of business permanently.

Then, what about travel? Most people understand that we won't get rid of COVID-19 until we get to herd immunity.

Then, what about travel? Most people understand that we won't get rid of COVID-19 until we get to herd immunity.

You can get there one of two ways, either through a vaccine or if you just allow 60 to 80% of the population to be infected, and then build up the immunity required to keep it from spreading.

-

What does that do to travel?

-

Not just foreign travel, but also, potentially even domestic travel?

We saw a huge outbreak in New York, and if there's another state, let's say Wyoming, that doesn't have a lot of cases and doesn't want to disrupt their economy, are they going to allow flights coming in from New York? Maybe, maybe not.

We'll have to wait and find out, but at the very least, you can see countries like Singapore and South Korea, who have handled this problem very well.

They have a very low case rate, and their case fatality rate is also extremely low.

Why?

Because they tackle this very strongly right at the beginning. Although their cases have flatlined, now they've opened back up, flights are coming back in, and guess what's happening?

The infection rate is going back up, not because people are spreading it from one Singaporean to the next Singaporean, but all the people coming in on planes are bringing it back in.

You see, this is not a problem where you just wake up one day and it's solved.

There are many variables that we have to think through. Again, let's say the services industry is hit extremely hard at a minimum.

Let's say travel is restricted on a moving forward basis until we come up with a vaccine, call it a year, 18 months. That also increases unemployment substantially, those are the most optimistic projections.

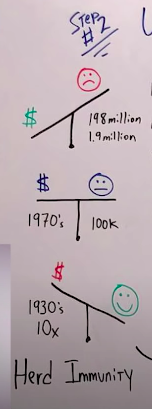

Here is a drawing where I've tried to simplify this as much as possible.

I've done the math on this, and if anyone thinks there's a different option other than what I've outlined, they just simply haven't done the math.

Option #1: Let the virus rip through the population as fast as we can to build up herd immunity.

With this option, you're doing as little damage to the economy as possible. You're overweighting the economy. To be clear, I think there would still be significant damage done.

There's no way of getting around that, but we're sacrificing the health of the general population. Now, let's put some numbers to it.

Let's be as optimistic as we can and assume we only need to achieve 60% herd immunity.

That would mean 198 million Americans need to be infected, okay? Well, if there's a case fatality rate of 1%, that means 1.9 million Americans would die.

That's not a very good option.

Option #2: Overweight the health of our population. This means going to the other extreme this way we're still going to have people dying. We all know that, but then, the economy suffers tremendously.

This is a total lockdown, a lot like they had in China.

That takes us to an outcome where, yes, we do save a lot of lives, but from an economic standpoint, we go into a 1930's style depression, but far worse.

I would call it 1930's 10X at a very minimum.

Just because we go through a 1930's type depression, it doesn't mean we have to go through a deflationary depression. We could very well go through an inflationary depression, and I think that is most probable.

Option #3: Not sacrificing health and the economy totally. It's a balancing act. But even there, we have a lot of fatalities and we have an unemployment rate that gets to the 1970s, if not higher.

In my opinion, this is the most probable outcome.

For those people out there that think we can go right back to business as usual, what you're not understanding is we have to build herd immunity.

Let's just say that we've all been shacked up in our houses for two weeks, and then we opened the economy back up on Easter, everything back to normal.

Well let's say we only have 10% herd immunity, so you're going to have another 50% of the population get it at a 1% fatality rate. You can do the math.

We need to understand that in the United States, if we want to have the same type of results as China, Japan, or South Korea, we need to take the same type of action.

We can't expect to have good results without taking any action. That's unrealistic. The math doesn't work.

If we want the same results as Japan, we need to make sure that every single person, the second they walk out the door, is wearing an N95 mask.

Also with China, if we want the same type of results, we'd have to go into total lockdown, just like they did.

South Korea, if we want the same type of results, we have to test 100% of the population or as close to it as you can get.

To reiterate, we cannot expect the same types of results as Japan, China, or South Korea if we don't take the same type of action.

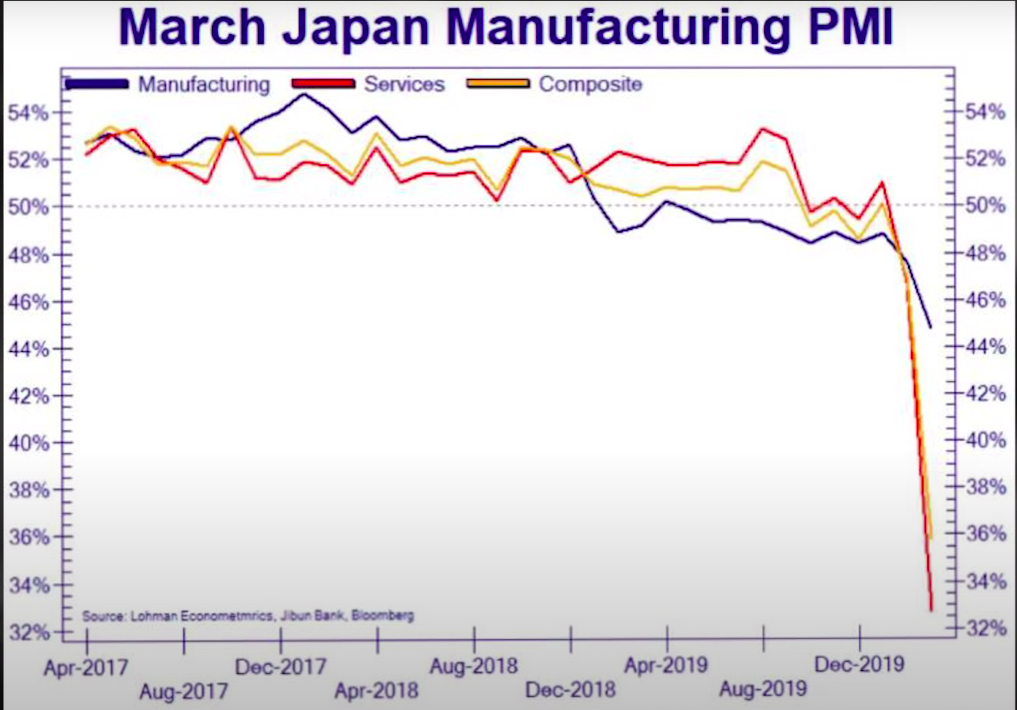

I also want to point out the Japanese economy has taken a huge hit. Look at the Japanese PMI.

This is the Manufacturing Index and it also includes services. It dropped off a cliff. The same thing happened in China.

Just because you're able to keep your economy going, while at the same time, getting the R0 value of COVID-19 as low as possible, it doesn't mean that it won't still crush your economy.

We go back to option#3, and we see the most likely outcome is for us to curve this, try to keep it under the capacity of the hospital system, but in doing so, we don't have a choice.

It's going to damage the economy, therefore, unemployment is going to get extremely high.

My Personal Investing Strategies

To be clear, this isn't investment advice, its just what I'm considering for my own portfolio.

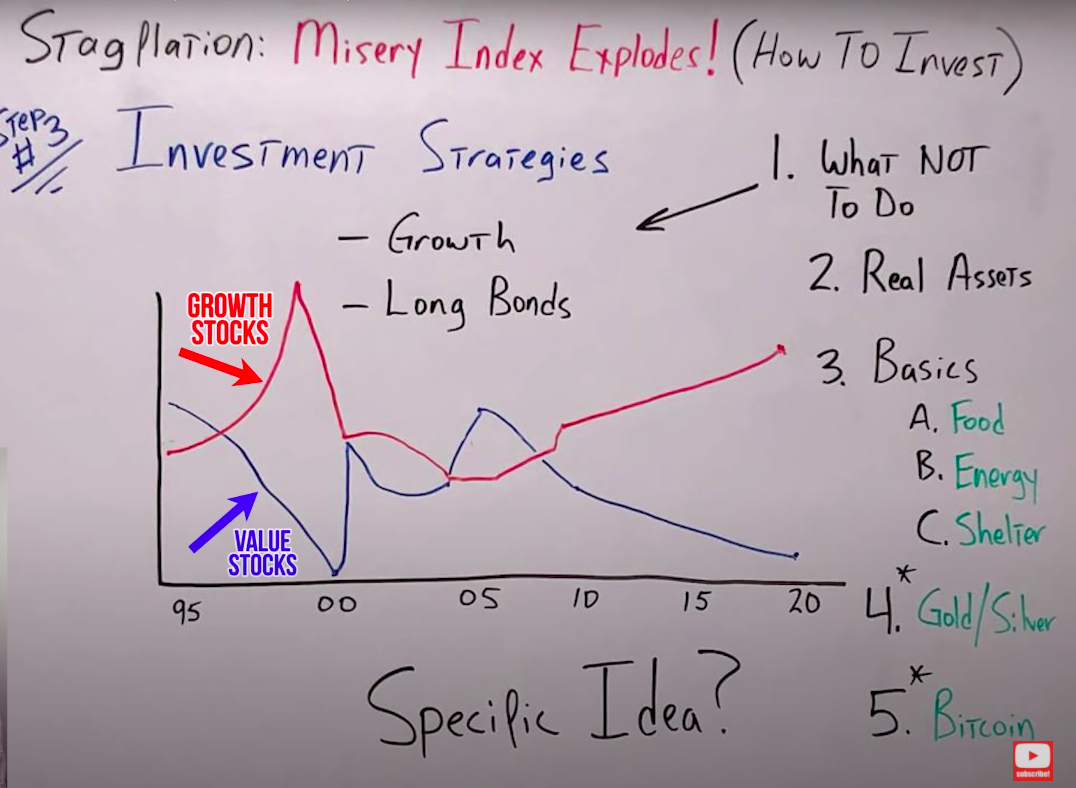

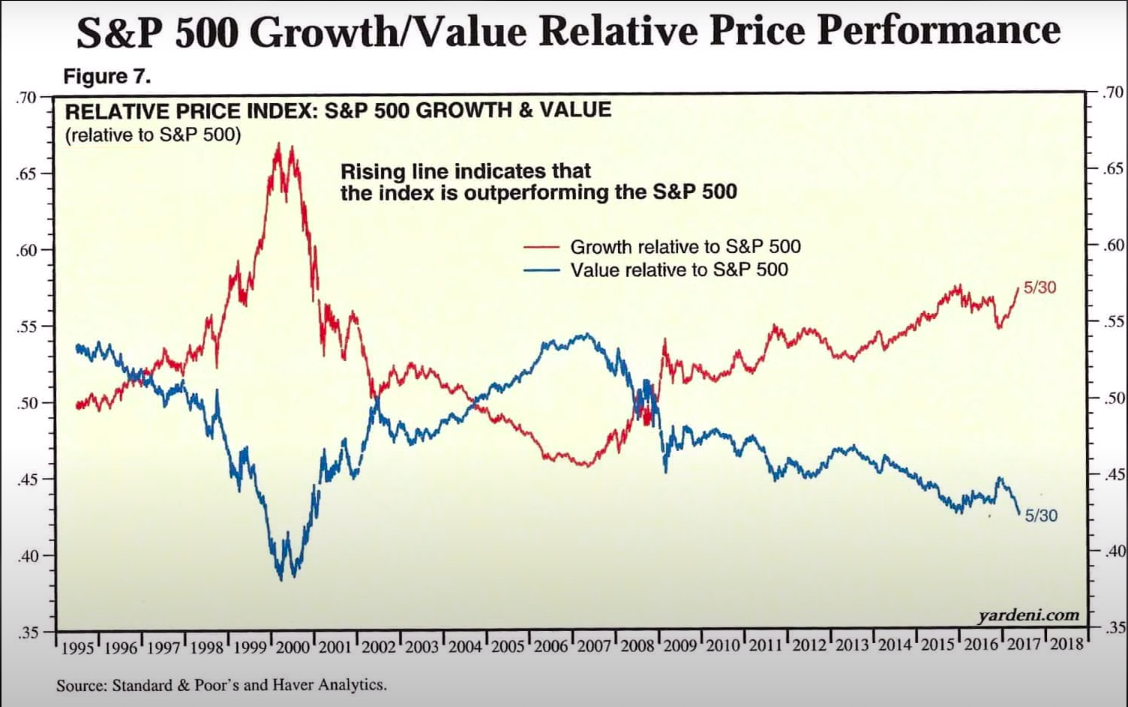

I start with a process of elimination. I try to figure out what I don't want to buy, to do so I evaluate charts. Let's check out a chart going back to 1995, all the way to 2020.

The red line indicates growth stocks, and the blue line, value stocks. This is relative to the S&P 500.

If the line is going up, it's outperforming and if it is going down is underperforming. From 2005 until about March of this year, growth did very well.

Value did poorly, so if I believe the economy is going to struggle, I don't want to own anything that's expensive, so you can take growth right off the list.

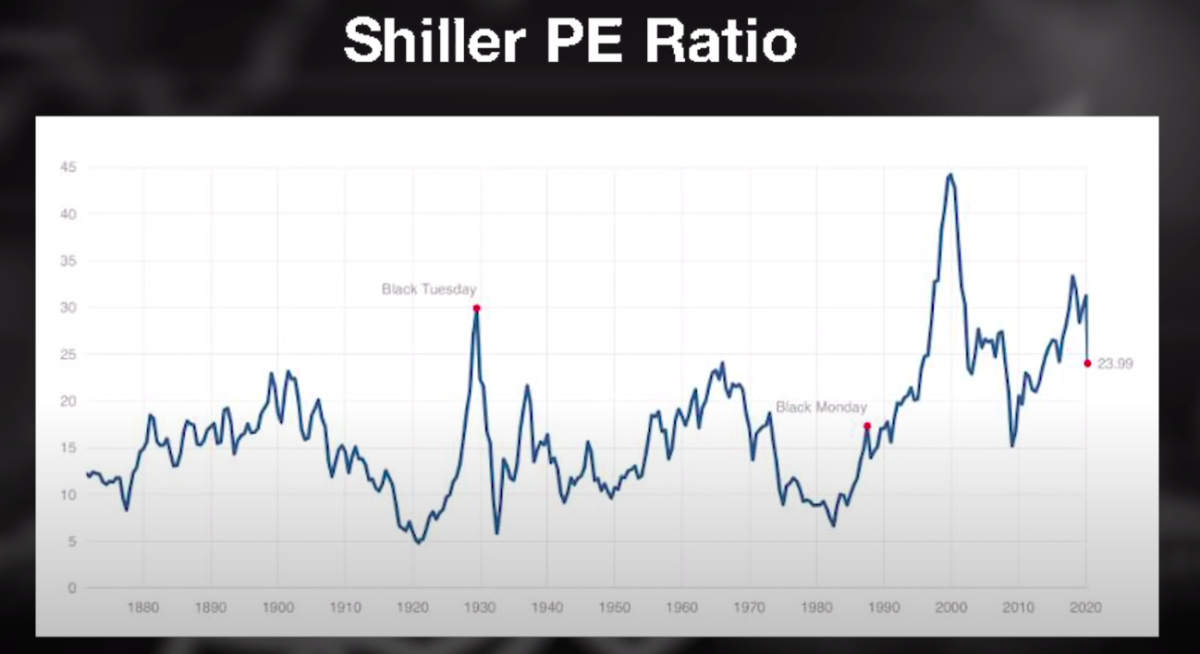

To be clear I don't like value either because I think the entire S&P is overvalued when you look at metrics like the market cap to GDP or the CAPE ratio.

Next, long bonds. Don't want anything to do with 10-year treasuries or 30-year treasuries.

It's not to say the interest rates won't go down and prices go up, but if we have a lot of inflation potential and the market perceives inflation coming down the pipeline, that's going to put a lot of upward pressure on the yields at the long end of the curve.

To be clear, the Fed could still take rates down to:

- 50 basis points

- 100 basis points

Who knows?

Just because they're taking interest rates lower, it doesn't mean that the interest rates in the long end of the yield curve will come down.

We could really start to see it steepen, and yes, the Fed could come in and try to peg the yield curve by printing a lot more funny money, but when the peg breaks, interest rates are really going to shoot higher.

That means you're losing value in the form of purchasing power when you're getting paid back the dollars, or you're losing purchasing power in the form of the value of the bond you own, going down.

Where do I see opportunity?

To dive into this deeper, look at a short piece of my full-length interview with former Fund Manager and Wall Street Insider, Chris MacIntosh.

He's great buddies with Brent Johnson and Raoul Paul. Brilliant guy. You're going to love the interview.

Chris MacIntosh: You're saying, “How are we positioning it?”

Largely, it's hard assets and it's valued overgrowth.

What I mean by value overgrowth is we're going to come out of this chaos.

When we crawl out of the car wreckage, that's when balance sheets are going to matter. That's when solvency is going to matter.

When we climb out of that car wreckage, we're going to also be in an environment where there will be more wreckages.

Because of the impact that is already taking place in the economy by shutting down the business. I don't quite think people fully understand how dramatic that's going to be. I was just looking at a survey done locally.

60% of small SMEs have 27 days that they could last with no income.

We're currently on the lockdown for four weeks. Now, to a certain extent, New Zealand doesn't matter, forget about us. This is taking place across Europe, across the U.S. People are still focused on the here and now.

Think about what will look like in four weeks, six months, and the flow-on effect. People are calling for a V-shaped recovery. I'm not sure they're looking at the numbers and thinking things through.

The one thing I'm about 100% sure of is that this won't be a V-shaped recovery, and in that environment, it's a massive contraction of productivity and supply of goods.

All the stuff that we've been looking at for the last few years have been decimated sectors, whereby there are little capital investments into them, valuations are extremely cheap, and now they just got cheaper, but they're also critical to society.

(End of transcript)

He talks about real assets, and I consider this the basics like food, energy, and shelter. Notice I said shelter. I didn't say real estate.

Why?

Because right now, I'm seeing them as two completely separate asset classes.

The shelter would be just the basics you need to survive, a roof over your head. Anything in addition to that, a huge backyard, a 5,000 square foot house in a super fancy neighborhood, or a penthouse loft in New York that's $5 million, that's an excess of just basic shelter.

I'm very bearish on real estate, but on shelter, not necessarily bullish. Yet, I don't think you're going to lose money in that asset class if we go into this environment of a poor economy with stagflation.

Obviously, I like gold and silver, but to be clear, gold as insurance, and silver as potential speculation.

Also, I like the asymmetry in Bitcoin, but I have another asterisk there. I'm very clear that Bitcoin, in my opinion, is not digital gold, it's not insurance, but it could be a very interesting speculation.

I know most of you right now are saying, “Wait, timeout George, you can't tell me all these concepts and ideas without giving me a specific example.

Something I can look into, something actionable that I can research before looking at the complete interview with Chris.”

Well, I don't want to completely let the cat out of the bag, but what I will tell you this. In the interview we discussed an ETF that's in one of the industries right here on the dry erase board, where the underlying assets have very little debt, and it pays a 13% dividend yield.

Make sure you check out the full interview with Chris you're absolutely going to love it.