Are We Heading Towards Stagflation?

Peter is the CIO of Bleakley Advisory Group, where he’s in charge of the investment management program, the firm’s investment philosophy, the global investment outlook, and asset allocation decisions.

He is also a CNBC contributor and Real Vision insider with great experience in macro, hedge funds, and financial portfolios.

In this interview, we dive deep into stagflation, market prices, commodities, oil, gold, and real estate. We also discuss how lockdowns and reopenings will affect our economy longterm, and if everything will be the same.

Join us in exploring this varied range of topics and learn from the best!

Some US economy stats —> Read More: https://t.co/Mqc9O09l5h pic.twitter.com/YIFMC00ERq

— Peter Boockvar (@pboockvar) June 23, 2020

Stagflation Is Coming

George: All right, guys. It gives me a great deal of pleasure to bring someone to the Rebel Capitalist Show, that I have a tremendous amount of respect for.

I love following him on Twitter, He's always got some incredible insights, he is the CIO of Bleakley Advisory Group, he's a contributor to CNBC, and he is the editor of the Boock Report.

His name is Peter Boockvar. Peter, welcome to the Rebel Capitalist Show.

Peter Boockvar: Thanks for having me on, George.

George: Now, I've been going through some of your more recent content, and I want to dive into that. I know you've been talking a lot about stagflation. Can you give us your thoughts on that?

Peter Boockvar: Well, I think that is what comes next.

Obviously with the demand destruction, the forced demand destruction, we've seen a shortfall in the prices of many things, but I think we're seeing a dress rehearsal of deflation of the stag that I expect to follow. I'll particularly highlight food prices.

Obviously, there has been major supply disruptions in a variety of different products, whether it's on the meat side because factories have had to close down or autonomy transportation side, where it's very costly to get a truck to deliver goods.

We've seen a sharp rise in food prices. What I expect to happen over the next six to 12 months as the economy continues to open up and rebound, is that the demand side will come back quicker, not quick, but quicker than the supply side.

Take the airline business, for example, I do think that with the help of masks and hopefully some therapeutics, people will get more confident to go on planes.

Not to the extent that they were in January, February, or in 2019, but you should see a steady increase in demand, but I think airlines are going to be very slow in bringing the supply back online, adding capacity.

You may be on an airline and may be full, and you're like, “What's going on here? But that's because I think a lot of planes are still going to be left in their hangers, which is going to mean higher prices.

Now, at some point, airlines will respond, they'll improve the capacity but I think there's going to be a moment where we're going to see this imbalance between supply and demand.

Peter Boockvar: You take a cargo shipping containers right now, their prices are up 25% to up to 40% more than where they were pricing in January, February because as things opened up, there's a rush to get things.

Imagine you're a manufacturer in the US and you source supply out of Asia, well, good luck getting a ship that's going to deliver it because there are about a million people that are in front of you waiting to get a product.

Which then forces you to maybe buy from a US supplier and then having to pay out more. You take oil prices, for example, we've seen a dramatic shutdown in production and essentially a collapse in Shell production in the US.

I think that we're setting ourselves up for higher prices in oil. I do think it's not going to just happen all at once. I think it's something that's going to build over the next six to 12 months after this current sort of deflationary period in the aggregate because of the collapse in demand. We are a consumer dependent economy, so you start to see a higher cost of doing business, then that's going to be passed on to consumers.

Then I'll also add from a small business perspective, you can imagine the higher cost of doing business in this COVID world, that even if you get a vaccine, there are still going to be things in place that aren't necessarily going to go away.

Just as they were after, 9/11 when you went through metal detectors and there were more checks and more security and so on, that's going to be the same here.

Peter Boockvar: There's going to be more cleanings throughout the day, businesses are going to have to retrofit their doors and their bathrooms, and a lot of different things.

Now, some of that's going to be one time, but it is a higher cost of doing business.

If a restaurant, for example, is going to only open up at 50% capacity, maybe get to 75%, well, chances are they're going to have to raise menu prices until they're able to get back to a 100%, which may not be until sometime next year.

I see a variety of cost pressures that are going to build. Then lastly, you can be sure that the fed and other central banks are going to way overstay their welcome with all this monetary larges.

I think that's also going to sort of be, well, it already is inflation tinder. Just a matter of what sort of strikes it.

Obviously the last 10 years it was more struck in asset price inflation. I think this time around It’s going to show up in consumer price inflation a lot because of what I just mentioned.

George:

-

How do you reconcile with a deflationists argument that velocity is decreasing, and the more debt you have, the more you have this velocity decrease?

-

If there is a lot of debt being paid off then it's reducing M2 potentially, and therefore causing deflation, how do you reconcile that argument?

Peter Boockvar: Right now velocity has collapsed, but M2 is off the charts and the upside to an extraordinary pace.

Again, the monetary tinder is there, which is a question of what match is struck now.

I think inflation historically, whether it's been popped up in the US, or Brazil, or other countries that have always had an issue with it, it's much more cyclical.

I think as long as there's technology and efficiency, there's a tendency to get more productive and have lower prices, but you do get bouts of inflation.

The thing about here is that, for years, we've had services inflation running at about 3% per year.

A lot of that had to do with rents and medical care but the cost of other types of services, whether it's insurance, general insurance, health insurance, tuition it's always been the good side that has offset that services inflation.

If services inflation can remain sticky, now obviously the rent side, you can expect rent growth to slow in this kind of environment.

But if the economy reopens and maybe rent growth still can continue on top of medical care growth and others, and then all of a sudden you start to get about of goods inflation.

Even if it's short-term, even though it lasts six months or a year, whatever, the combination could lead, just statistically, to higher inflation.

In a consumer dependent economy, you get a higher cost of living, that could be the stag part.

George: What we've had is the stuff, goods, and services, that are produced domestically.

We've seen inflation, while at the same time, the stuff that we've been importing or the goods from other countries, we've seen deflation that nets out.

Peter Boockvar: Well, the good side, just generally, whether it's the stuff that we import or stuff that we manufacture here, there's been obviously pressure on the good side, that if you get any lift there.

Enjoying that with sticky services inflation, then you're going to have an uptick, just statistically, in the aggregate inflation stats.

Prices Are Not Black And White

George:

Do you see certain prices coming down, such as things that you need credit to buy, like higher-end vehicles, or homes, some things like that?

I want to get into real estate deeper, later on the conversation.

The reason I asked that is because I think when we're looking at inflation-deflation.

A lot of people just try to throw this blanket over the whole thing and say, okay, prices are going up, or prices are going down like it's black and white, but often it's very nuanced.

Like you were saying before, a lot of prices can go up, while at the same time, some things are coming down, and it's just a matter of what's happening when.

Peter Boockvar: That's why I like to make the distinction between services and goods because people tend to really look at things in the aggregate.

If I live in a city and I don't need a car but I'm renting, well, the cost of my living is going to be higher than maybe someone in the suburbs who owns a house, has a low mortgage rate, and drives, but gasoline prices are low.

Inflation means different things to different people. If I'm someone who's building a 401k, and all of a sudden, I enter the market at all-time record highs, well, the asset price inflation is good for existing holders, but it makes me forced to pay a higher price.

Home price inflation It's good for the owner, you can build equity, but a five or 6% annual home increases that we saw for years over the last five years makes it difficult for the first time buyer who has limited resources.

Doesn't necessarily have all the money for a down payment, and they're paying very high prices for home because the fed wanted to juice the housing market with low-interest rates.

The first time buyers sort of got priced out, forced them to rent, and they're paying 4% to 5% annual rent increases.

George: Yeah there's a big difference there between asset prices as well. I like to point out back in the 1970s, from '72 to '74.

I believe the stock market went down by almost 60%, while at the same time, you've got CPI running at least 5% or 6%.

How do you take your view and translate that into a view for the dollar, the DXY, against the Euro, the yen, etc?

Peter Boockvar:

Just as I like to look under the hood within inflation, I also like to do the same with the dollar, because a lot of people say the dollar's up, and the dollar's down, dollar's strong. To me, you have to really splice up the dollar’s behavior against different currencies.

The dollar strength, over the last couple of years, really has been against the troubled countries of Brazil, and Argentina, and Turkey, and Mexico.

You look at it against Canada, the Canadian dollar has been trading between 135, 145 for years.

Look at the Euro, Euro has everything against it with negative interest rates, sclerotic economies, massive debt, troubled banking system because of negative interest rates and no yield curve, political issues.

I'm trying to merge all these different countries. The Euro has been trading between 105 and 115, outside of a spike to 125 in 2018, for about five years now.

I'm trying to merge all these different countries. The Euro has been trading between 105 and 115, outside of a spike to 125 in 2018, for about five years now.

Look at the yen, look at what the bank of Japan has done. Negative interest rates, a balance sheet bigger than the size of GDP, and the yen trades great.

The pound got slammed after Brexit, but never really broke 120, and it has been in a range for the last couple of years.

The dollar still has its own flaws, largest debtor nation in the world, exploding deficits here, which is big strikes against it.

I understand, on the other hand, people like to call it a dollar shortage where there's a scramble for dollars from international countries, because of whether they need dollars just to transact or where they have dollar-denominated debts.

The analysis, it's not being done as they also have a lot of dollar-denominated assets as predators of the US.

I think the dollar trades okay against some currencies. Trades great against the Chinese Yuan of late, certainly, but doesn't trade that great against the Euro with all the issues that the Europeans are facing.

George:

If we're just looking at the DXY, your view is it's probably going down as well as this stagflationary environment.

I've tried to think it through a few times in some of my videos and I've tried to say, well, can we have this situation where we've got CPI going up, or what it will admit to, 5%, 6% per annum, while at the same time, the DXY is going actually up to 110 to 120, which again, people see it as this monolith.

It's only binary, but I don't know, maybe there could be a situation where we see both, and it kind of blows people's mind. What do you think about that?

Peter Boockvar: The Euro heavy dollar index, as they call it has been given every gift from the other countries, the other cross rate countries to really spike above 100 and hold it.

We're really no higher than we were five years ago, the dollar has essentially just been in a gigantic trading range.

I don't know what more of a gift you can hand the dollar in terms of the flaws in the other currencies to get the dollar to rally from here.

I'm more inclined that in that type of context, the dollar is more likely to go down and up.

George: The bulls are going to point to QE though, the bulls are going to flip it and say the same thing that the Fed's taking its balance sheet to 7 trillion, you've got M2 going through the roof and the dollar has still been able to stay close to a hundred.

Peter Boockvar: Yeah, that's very true. We're all in this same QE soup together.

Not like we have outdone the Bank of Japan or the ECB, The Bank of England is essentially now directly monetizing the debt in the UK.

We're all debt actors here, and you're just talking about one crappy Fiat currency against another.

Commodities In A Fiat Madness World

George: All right. Let's shelf the crappy Fiat currencies for a moment and let's talk about commodities, gold, silver.

I actually heard you talk about copper the other day as well, which I haven't heard a lot of people talk about.

Could you give me your views on just that whole commodity space?

Peter Boockvar:

I look at gold, not as a commodity, but a currency, since most of its demand is jewelry and investment.

Whereas silver is sort of half and half, about half of silver's demand is industrial.

In secular industrial growth drivers, such as electronics, batteries, and cell phones and EVs, whereas a lot of the silver demand used to be just camera film, but obviously that went away, and then the other half being jewelry and investment demand.

I find silver pretty interesting playing on both sides that it'll benefit as the globe improves. Just by reopening, the global economy is going to get better.

I'm not saying it's going to be good, but it's still going to be better than when you shut everything down.

Also, it's still got 4,000 years of financial history as money. In a Fiat madness world that we're in, gold and silver should benefit.

Copper, what I find interesting about copper is its usage in a lot of secular growth drivers.

Just building an EV car relative to a combustible engine car, you can use five to six times more copper than you would in a regular car.

Now, copper obviously had a big run in the 2000s as China built an apartment after apartment and all the infrastructure spending that needed copper.

The apartment building stuff is going to slow, but there's still a lot of infrastructure spending in China, but there's also going to be, when we come out of this, and it started already, huge infrastructure spending in India.

I really like the growth drivers of copper here in a lot of secular areas of growth that I see, supply-demand was uneven going into COVID, where you had not enough supply relative to the demand.

Now, obviously you see a big collapse in demand, that gets back into equilibrium, but on any economic recovery, I think the supply side is going to come back at a slower pace so I think that you could get a nice rise in copper prices.

George:

What do you think about oil and uranium?

Peter Boockvar: Oil I think is very interesting also, as I mentioned early, you've seen a collapse in the pace of production, you've seen US Shell that has just gotten decimated.

Even if oil gets back to $40 to $50, it's going to take a long time for a lot of that drilling to come back because a lot of these companies are not going to get financed by anybody because of the pain they felt in 2015/16 after oil prices collapsed late 2014, and also what just happened now.

You can imagine the projects that are getting canceled, Deep Water, ever since 2016. When I saw negative prices on that front-month contract, I just felt that that was what bottoms are made of.

We obviously still have to get more demand here as the economies open up.

I don't know if oil jumps at the backyard of this year, or it's 2021 story, but we have sentenced in motion a major imbalance between the supply of oil and the demand for it.

Now, obviously looking over time, there is a secular decline in the demand for oil as we shift to other sources, but at least in the next couple of years, there is going to be an imbalance.

Uranium, I follow uranium because I own Cameco, so I've been wearing that around my neck for years, that dead weight.

We've certainly had a big jump in uranium prices from the low 20s per pound to almost $35 a pound, Prior to COVID, obviously, Cameco shut things down and other countries and other companies did the same.

That was accelerated in the colder world, where even Kazakhstan has shut down more and Cameco shutdown Cigar Lake, and we've had also a bunch of others.

I think that there's a major supply-demand imbalance headed our way.

It's already now happening but should accelerate in the next couple of years. I do expect much higher uranium prices that companies like Cameco should benefit from.

When Times Are Tough, Oil Goes Over Green Energy

George:

What do you think about the political narrative, and maybe the societal narrative, for green energy over the next two to three years, assuming that we go into a substantial recession, if not a depression?

What I mean by that is, when times are good, we can say, yeah, let's throw all this cheap money at green energy.

It might be the right thing to do or the wrong thing, I'm not here to dispute that, but when I've looked through oil, or thought about it, I said, boy, if you got a lot less people focusing on green energy and spending money.

They're investing their because money's tight, we're in a recession, the politicians have a lot bigger fires, let's say, to put out, or more urgent fires.

Maybe it just gets put onto the back burner, while all of a sudden you've got these big oil companies and all their competitors are going out of business, not just in the green energy space, but in the oil space itself.

Maybe that reduces a lot of the supply, maybe that could be a tailwind, a headwind. Have you thought through that?

Peter Boockvar: No, you make a good point that when things are good, people can get creative, so to speak, with how they want money spent and all the big picture ideas, and wind and solar are going to run everything.

George: They got to go so far out the risk curve, the pension funds, and everybody.

Peter Boockvar: Right, but when things get tough, you start to focus on more things that are imminent, that are right in front of your face.

Particularly, from a constituency, most people are going to be worried about having money to put food on their table, rather than whether they are going to charge their car with a battery or fill it up with oil, or gasoline.

They're going to make the decision that is cheapest for them. If it's cheaper to buy a combustible engine car relative to an electric vehicle, well, when times are tough, that's what they're going to do.

Gold As Mean To Staying Rich, And Maybe Getting Rich

George: You said it a lot better than I did.

I know a lot of my viewers are really interested in gold and silver, but an area of confusion that I see a lot of times on my live streams is, if gold goes to 10,000 an ounce, let's say, or 20,000 an ounce, or whatever, if you own gold, you're going to get rich.

What I always try to tell people, and this goes back to stagflation is, maybe, but maybe not.

I'm the biggest proponent in gold bull out there, but I also like to give people a dose of reality, that if prices go to 10,000 an ounce, let's say, in nominal terms, and then you go to sell your gold, you're going to get taxed.

Let's just say they'll probably take long-term cap gains up to the income level, the tax goes up to 30% or 40% on that.

Now all of a sudden, you're paying a 40% tax, but you haven't increased your purchasing power at all.

Peter Boockvar: You're assuming that people get their gold and silver exposure through maybe an ETF, but I don't know any other way. It's still even on probably an after-tax basis, you will still protect your money over time.

George:

Yeah, that's usually the point I try to make to the viewers. I think gold is fantastic to stay rich, but to get rich, it might or might not be.

Peter Boockvar: Right, a lot of it's getting the timing right. Look at going into 2013 when we had QE infinity, If you look at a playbook, if you had it, you'd say, wow, this is like the ultimate play.

The gold, which topped out in 1900 and September, 2011, consolidated, pulled back, came in a couple hundred dollars an ounce and QE infinity was like the ultimate final send-off into a parabolic move to 3,000, 5,000, 10,000, whatever you want to call it, and obviously the exact opposite happens.

The more the fed printed, the lower gold went and higher stocks went, because people felt that, well, why should I own gold when I can own stocks if the fed has my back.

Now, we are obviously in a somewhat similar situation. The QE infinity is now a global phenomenon, negative interest rates didn't really exist in 2013, now there are, unfortunately, part of the landscape in Europe and Japan.

You have obviously a short drop in real interest rates and nominal interest rates and the dollar, which again, is just chopping around here, not really showing much strength.

One of the characteristics of '08 when the whole global economy is collapsing, because of the financial system, everyone ran to the dollar, and the dollar had an extraordinary rally in 2008.

The dollar rally this time around, it was kind of lame when you think about it compared to the last economic downturn.

I think that also says a lot about the dollar, but yeah, I guess to your point about owning gold and silver on an after-tax basis, it's one thing better than the other, and probably.

I think the hope is if he owns a coin, for example, maybe at some point you sell that coin and you get it for dollars and you can buy whatever you need with the dollars.

The tax implications, if you can spread out over time, it can sort of be deferred in a way.

George: Yeah, exactly. Also going back to the negative interest rates, I guess if you're looking at gold as a currency and you've got a negative, and that's always the knock against gold is it's got this negative carry, but if you've got an even bigger negative carry with negative interest rates, then all of a sudden, those look pretty good.

Peter Boockvar: Right.

Gold has, technically, a positive carry against a negative-yielding security, or no carry difference between something that has no interest rate.

When you think about the trillions of dollars of negative-yielding debt, gold's got a positive carrying value against all that.

Changes On Consumers Behavior Due To The Pandemic

George:

-

How do you see the virus playing out with people going back to work?

-

The United States is opening up. Do you see us maybe getting a second wave?

I know you're not a virologist or anything like that, but just from a human psychological standpoint, do you think that people are going to go back to work?

Everything's going to be back to normal, back to usual, or do you think there's going to be a trial period where people are a little hesitant and maybe not behaving the way they used to?

-

Do you think there are some behavioral changes that we'll see for decades to come?

-

Or, that combined, if we do get a second wave, then how does that affect people psychologically?

-

Then how does that translate into the economy?

Peter Boockvar: Well, if what I hear is true, that this can somewhat be seasonal, it'll calm down during the summer and then flare up again in October, November, well then yeah, we'll have a second wave.

I just think that we'll be much better prepared for that second wave. We've already altered behavior, we've put in widespread testing capability, we'll be better able to handle it, but I think, to your main point, consumer behavior is certainly going to change for a period of time.

Even if we do come up with a vaccine tomorrow and we're all vaccinated, I do think that there is going to be maybe more of a desire to save more as a consumer, save more for a rainy day.

Companies will probably try to do more with less in terms of labor. They will be maybe a little more cautious with respect to their capital spending.

Maybe there'll be focused more on their balance sheet, which means less stock buybacks.

I do think there's going to be a change in behavior and If I'm right on the inflation side, and if we get a vaccine and growth comes back, I do see an inflation issue.

This means that all these central banks are going to have to start figuring out how to start pulling all this liquidity back and getting out of negative rates or zero rates, and not necessarily shrinking their balance sheet, but not letting it grow anymore.

That's going to create its own challenge, we can go from one challenge, that being battling COVID, to facing another challenge.

Because when you think about the accesses over the last 10 years, it was basically a central bank induced credit bubble that manifested itself mostly in sovereign bonds.

But sovereign bonds being the risk-free rate, everything is priced off that risk-free rate, therefore, you can argue that everything was inflated.

Maybe we end up having a popping of that ultimate bubble once we somehow hopefully get over a COVID and have an economic rebound again.

George:

How much damage do you think has been done to the real economy though, from a standpoint of businesses, just that won't come back?

The mom and pop restaurant, or the gas station, or the dry cleaner. Sure, we've got the airlines that'll probably be there because they've been bailed out, but how does it work with just main street? Are 90% of those businesses going to come back? 50%? 100%? What do you think?

Peter Boockvar:

Unfortunately, the lives of these businesses are dependent on who their governor is, unfortunately, and who in that state is making this decision.

If you happen to live in Georgia with a small business, well, you got lucky, because you were able to open up your barbershop a month ago.

Now, if you're unfortunate to live in New Jersey like me, well, they still can't tell you when you can open up your barbershop.

Las Vegas casinos are opening next week, and New Jersey can't figure out a way to open their barbershop.

They'll allow Costco to open and all the craziness that's going on there, but the local clothing store that probably has no more than three people at a time, New Jersey won't let them open.

These governors, they're playing with fire here the longer they go without letting these businesses reopen.

If they can get religion somehow in the next couple of weeks, it will determine how many of these small businesses will live or survive.

But even if they survive, again, a restaurant isn't just going to barely make it at 75% capacity. Who knows when they'll get to a hundred?

You can be sure that also the cost of doing business is going up, so companies will be less inclined to hire everyone back, and this is going to take time.

It was a traumatic experience, you can't just expect a fast rebound from something like this. It's going to take time to heal.

The Economy’s Demand Side Will Recover Quicker Than The Supply Side

George:

Peter, going back to what you were saying about inflation and the destruction of supply, I think that's what so many people ignore.

They focus on the demand side of the equation, but they just don't even think about the supply side as though it's always going to be at a consistent level.

Like the velocity of money like Milton Friedman back in the '70s or something like that.

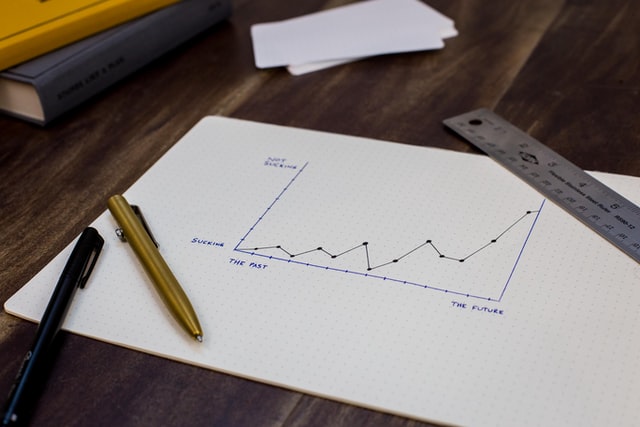

I went back and looked at a chart of deflation going back to probably 1800, or so, in the United States.

I noticed, prior to the 1930s, you would have inflation go up, you'd have deflation, It just looked like this wave thing, almost like a heartbeat just going up-down, up-down, up-down.

Once we got to the middle of the 1930s, it was just almost all inflation. Everyone, so you'd see a little bit just a dip down like we had in 2008 or 2009, but it was only for maybe a quarter.

I tried to think, okay, what happened? What changed there? I don't want to assume that causation is a correlation I don't want to get that confusion.

But in the middle of the 1930s, they instituted unemployment benefits, social security payments, and then at the latter stages of the 1930s, they had the minimum wage.

I was saying, okay, well, if we've got a minimum wage, and now all of a sudden, maybe businesses can't lower their prices too much, so they go out of business.

If you have less supply, you have more supply destruction, while at the same time, you've got an artificial component to demand because the government has a transfer mechanism to get money into the back pockets of people that will actually spend it.

Do you think there's anything to that?

Peter Boockvar:

No, that's basically a key part of my thesis, is that the demand side will come back and hold up better than the ability of the supply side of the economy to deliver.

Also, just look at wages, If you keep unemployment benefits elevated, which we certainly are doing through July, companies are going to have to pay higher wages to convince employees to come back.

If you think about in New York, where you get the extra $600 on top of $400 of unemployment benefits, you going to be making a thousand dollars a week on unemployment.

Well, on a 40 hour work week, that's $25 an hour. A lot of people were making maybe 15 prior to that.

Now, granted that's set to expire at the end of July, but you can be sure they're probably going to extended this in some fashion.

George: Election year, for sure.

Peter Boockvar:

Employers are going to have to pay more wages to get the right people back into these jobs.

George:

Going back to the fed and unwinding their balance sheet, or the interest rates being artificially low for so long, how does that affect an economy long-term?

I've spent a lot of time in South America, and one of the countries I spent time in is Ecuador, where they dramatically subsidize the price of fuel.

Not to the extent that Venezuela did, but let's call it 75 cents a gallon right now.

They've had this for decades, or, well, at least 20 years in Ecuador. If you went to the population and said, okay, we're going to go ahead and just jack prices, well, the market take control here, and the price of fuel is going to go from 75 cents a gallon to, call it $3 a gallon.

Not only would you have riots, but the economy would just implode because it's been built around this artificial subsidy.

If I look at interest rates that they're the cost of money, and money is one half of every single transaction, the fed has manipulated this.

Could we have built our economy around these artificially low-interest rates and expansion of the Fed's balance sheet like Venezuela or Ecuador did with the subsidy of fuel?

Peter Boockvar: I guess, we could. But I don't know how you keep something like that together.

George: That's my point.

Do you think we have to where, if the fed now lets interest rates go to a market price or tries to do QT to decrease their balance?

Now, our economy has been built on it, and it's been built on high asset prices as well. Does the economy really struggle, I'm not going to go so far to say implode, but really struggled, just like it would in Ecuador allowing the market to take gas prices up to $3 a gallon?

Peter Boockvar: What you're talking about is, do price controls work? Price controls and the suppression of interest rates is another form of price controls.

I guess they can work for a period of time, but then you create these massive imbalances that eventually correct themselves.

Price controls, over time, have proven to be epic failures. You just have to look at that, whether it's the interest rate lever price controls, or wages, or whatever, or oil prices, in the examples that you gave, eventually it blows up.

It blows up, whether it's a government budget that blows up. Argentina tried to get off a lot of these subsidies, which was the right thing to do overtime, but they ran out of time in the sense of the market giving them time, and they declared bankruptcy for the ninth time.

It's something that never ever works over a longer period of time.

Real Estate Today: A Mixed Bag

George:

What are your thoughts on the real estate market?

Peter Boockvar: I think it's a mixed bag, Obviously the office space is going to be challenged for obvious reasons.

I think multifamily, depending on what area of multifamily you're in, some will do better than others.

I do think as employment does come back, multi-filament should be okay because there are going to be some people that just can't afford to buy a house, and they're going to rent, but maybe they rent a single-family home instead of buying one.

Obviously, the industrial area of real estate will probably do well with e-commerce. It's going to be a mixed bag. I think the heyday of real estate, in certain areas, is probably over in the cycle.

Yes, low-interest rates are certainly a help, but you have now everyone rethinking the purpose of real estate.

The movie theater that I own, that's real estate, Leased AMC theaters, is that going to be the same type of asset it was before? I don't know.

We'll have to see how consumers change their behavior or not. I do think that memories are short and like the average Friday night, people are going to want to go see a movie again, but it's going to take time to eventually get that to happen.

While some things are going to change, maybe they don't change that much.

-

Residential Real Estate

George: What about on the residential side?

Peter Boockvar: I think it's interesting.

George: As in apartments, like single-family.

Peter Boockvar: So single-family, obviously a large and key factor is obviously the unemployment rate. You're not going to go out and buy a house if you don't have a job.

Where that goes is going to be important. The demographics of millennials who maybe were living in cities, maybe they want to move to the burbs after this COVID experience.

Seeing pretty steady demand for new homes priced at low price points of under 300,000.

That's actually been an area where there's been pretty steady demand, but on the upper end, I really don't want to be in, this is more multifamily, but apartments in New York City, I'm sure are going to be under stress.

Housing and in California, where taxes are through the roof, and who knows what their economy is going to look like after this reopening, may not be attractive.

But, single-family real estate in Arizona, Nevada, Texas, and Florida, where it's more affordable to live and the climates are much better, well, their real estate markets and residential real estate markets would probably be better off than others.

-

Stagflation In Residential Real Estate

George:

How do you factor stagflation into the residential real estate market from a standpoint of the builder’s costs increasing substantially?

It might be increasing faster than people's incomes because, at a certain point, you can only take mortgage rates so low.

Now, we've had this benefit since the early '80s, where mortgage rates just go down and down, making those monthly payments more affordable, but at a certain level, they can't really go down any further.

Now it goes back to being based on your income, and if incomes aren't going up, but the cost of the commodities, basically to build the home, is going up at a faster pace, what do you think happens there?

Peter Boockvar: Well, builders have certainly been squeezed for years now with the higher cost of lots of regulatory, compliance, and labor costs.

When we had a 3.5% unemployment rate, good luck finding a fresh construction crew, good luck finding out electrician on the day that you needed it.

That is why a lot of these builders were focused on higher price points because they thought, if I'm going to build a house, I might as well do it at a higher price point.

Therefore, there was a lot less supply in the area where the most demand was for homes priced below 300,000.

That would be able to compete against the multifamily, where a lot of first time home buyers who couldn't afford a higher-priced home or couldn't find it a down payment for that, were forced to rent. Any relief on the cost side will certainly help.

I think some builders are getting more efficient in being able to deliver a $300,000 house at a profit margin that's acceptable.

I think that those that will be able to do that could do fine.

I question whether some of the higher-priced points will do okay if the economy is still pretty sluggish.

Now, yes, you're going to get some transplants out of the city, and they're going to want to move to the suburbs, so there's going to be some demand there, but over time, you're going to need higher incomes, higher employment to a really convinced people to own instead of rent.

The Future Of The Pension Funds

George: I know you're pressed for time, and I really appreciate the generosity of your time so far, it's been a fantastic conversation.

I want to ask you about pension funds before we go. I know your good friend, Danielle DiMartino Booth, I interviewed her the other day, fantastic interview.

I understand her view, and it makes a lot of sense.

According to https://t.co/lLIQw7Sq0U, listings were down by 30% in early May over the prior year. They are still down a hefty 21% and are unlikely to shrink much further.https://t.co/0j9jpuDhU0

— Danielle DiMartino Booth (@DiMartinoBooth) June 17, 2020

Do you have a view on the pension funds or what they look like in a year, three years, or five years?

Peter Boockvar: Yeah, Danielle, a dear friend, has been all over this story and has been highlighting it, for now, years.

In this kind of environment, everything that she's talked about really gets exposed here because of the collapse in revenue.

And just a higher cost of expenditures, particularly on the pension story with meeting pension obligations, whether it's healthcare or just paying out the obligations that they're committed to, on top of the growing piece of the budgetary spending going to Medicaid.

You can only imagine with post-Obamacare where Medicaid expansion grew to such a large extent, that between those two, you're leaving yourself very little money for everything else.

We know the states that are troubled, this situation has just made it that much worse. The question at this point is, who's going to get clipped?

Bondholder thinks that they're protected here, but when push comes to shove, if there's a municipality, whether at Chicago or Illinois as a state, and they're going to try to figure out in these loan docs, who am I going to clip?

They're going to do their best to make sure that it's the Muni bondholder rather than their pensioner that they promised the sky to for the past 30 plus years.

George: All right, buddy. We'll go ahead and end it there, fantastic conversation.

Peter, I really appreciate it. For my viewers who want to find out more about what you do, I know you've got some fantastic research on your website. Where can they go to check that out?

Peter Boockvar: I write daily subscription newsletter type model, boockreport.com, and a CIO of Bleakley Advisory Group, if they're only interested in financial services help, they can call us and see our website at bleakley.com.

George: Awesome, buddy. I appreciate it, again. Can't wait to do it again.

Peter Boockvar: I appreciate you having me.