Inflation or deflation? To predict the future of pretty much everything, you need to answer this question in your own mind. This will also help you determine what's going to happen with the dollar, stocks, bonds, gold, and real estate.

There's a huge debate around the effect quantitative easing has in the system: Does it produce inflation or deflation? To answer that question I'll explain what the two main voices on FinTwit say about it.

In this article, I explain how you can see what's ahead, but because this is part one of a series, I encourage you to read the whole thing. Here, I explain the first two steps, and the next one you can read it by clicking here.

Brent Johnson And Steve Van Meter's Approach: QE Is Deflationary

-

Is the process of quantitative easing the complete opposite of what everyone thinks it is?

-

Is it deflationary?

-

Does it pull liquidity out of the system?

There are two main voices for this view right now on FinTwit and this is a huge debate going back and forth. Two of my really good buddies I've got a tremendous amount of respect for, number one obviously, Brent Johnson, then the bond king Mr. Steven Van Meter, both believe that bank reserves are not a medium of exchange.

I'm going to start with that premise and then move on from there.

If bank reserves are not a medium of exchange, what purpose do they hold?

In their view, the only thing the bank reserves held at the Fed can do is facilitate more lending. It increases the balance sheet capacity for the commercial banks.

A simple way to look at it is, if they have one additional bank reserve, now they can create an additional loan. It's not a one-to-one ratio or anything like that, it’s just that is a good way to look at it.

If you have another bank reserve, then you can make another loan. If you have one less bank reserve, that's one less loan that you can make.

I'm just trying to oversimplify it so you get your head around it. The main takeaway in their view is bank reserves can only be used to create additional loans by the commercial banking system.

It is very important you understand this for the rest of the article.

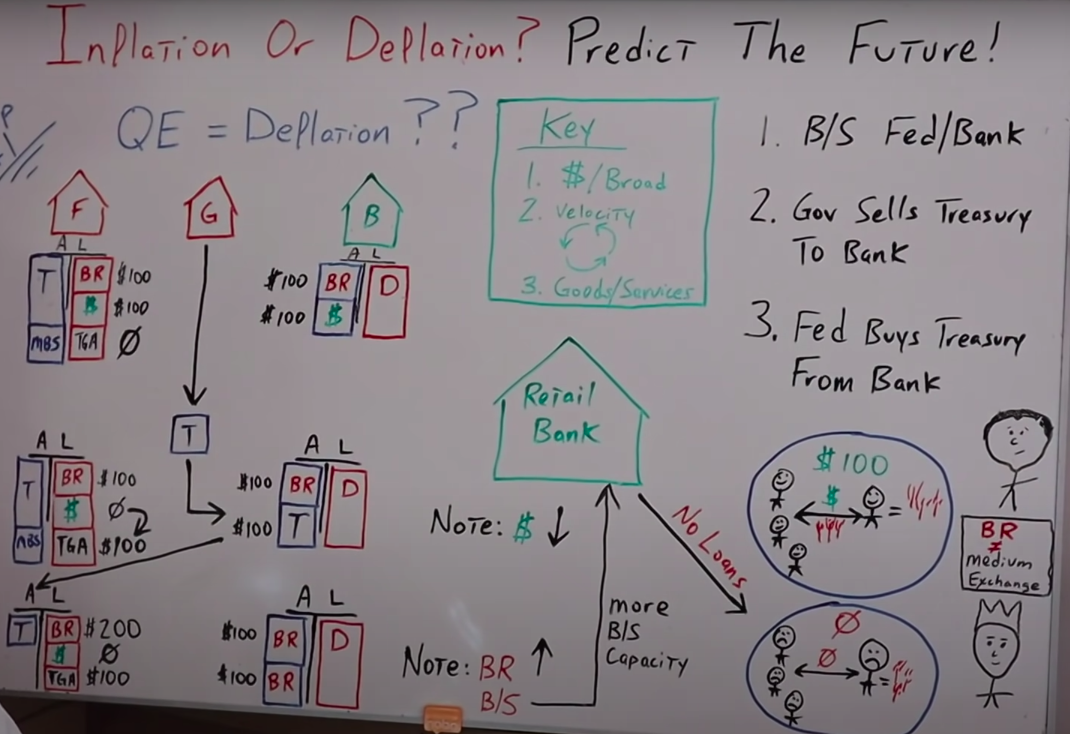

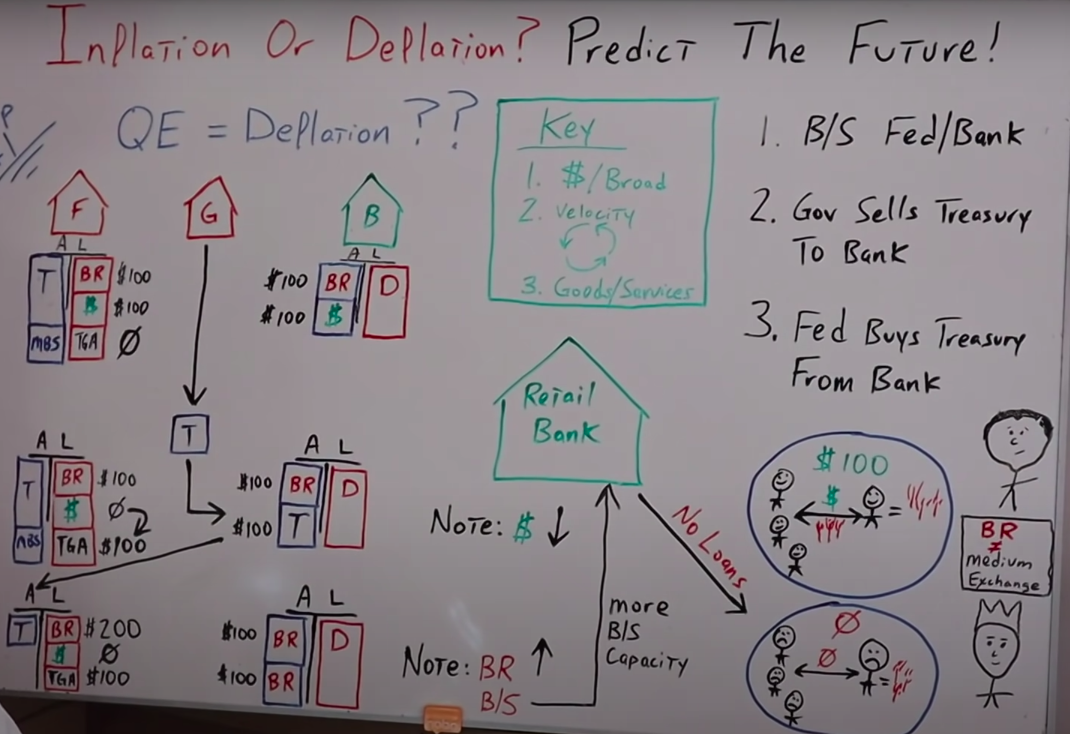

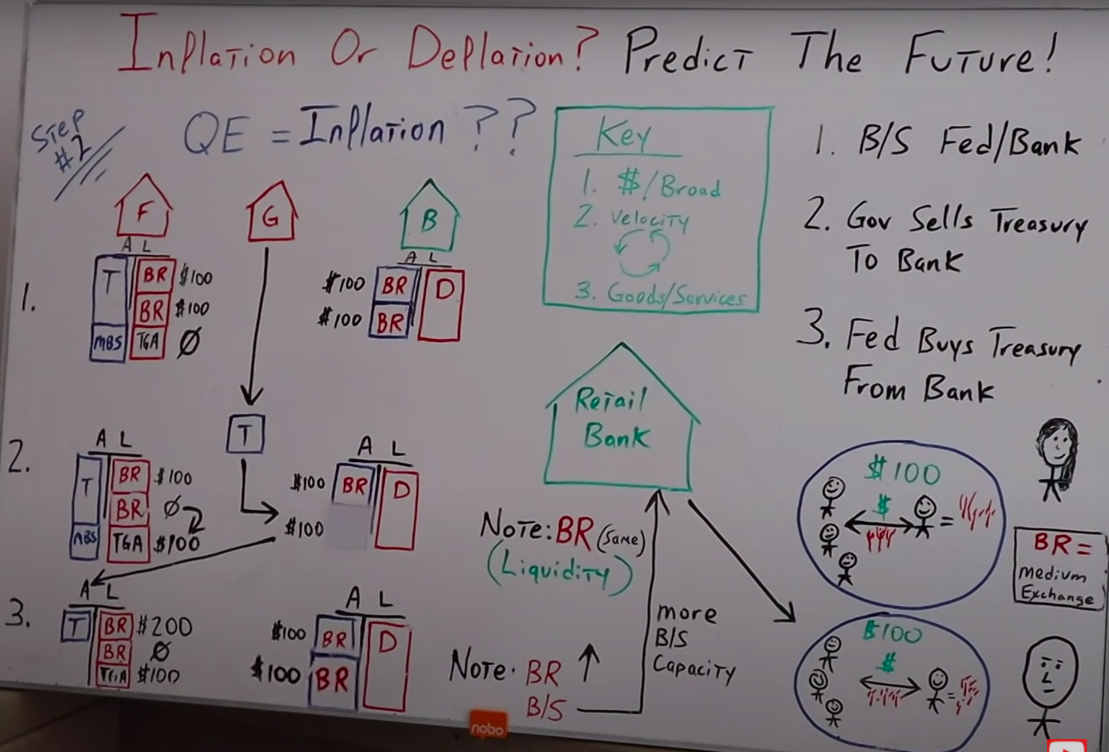

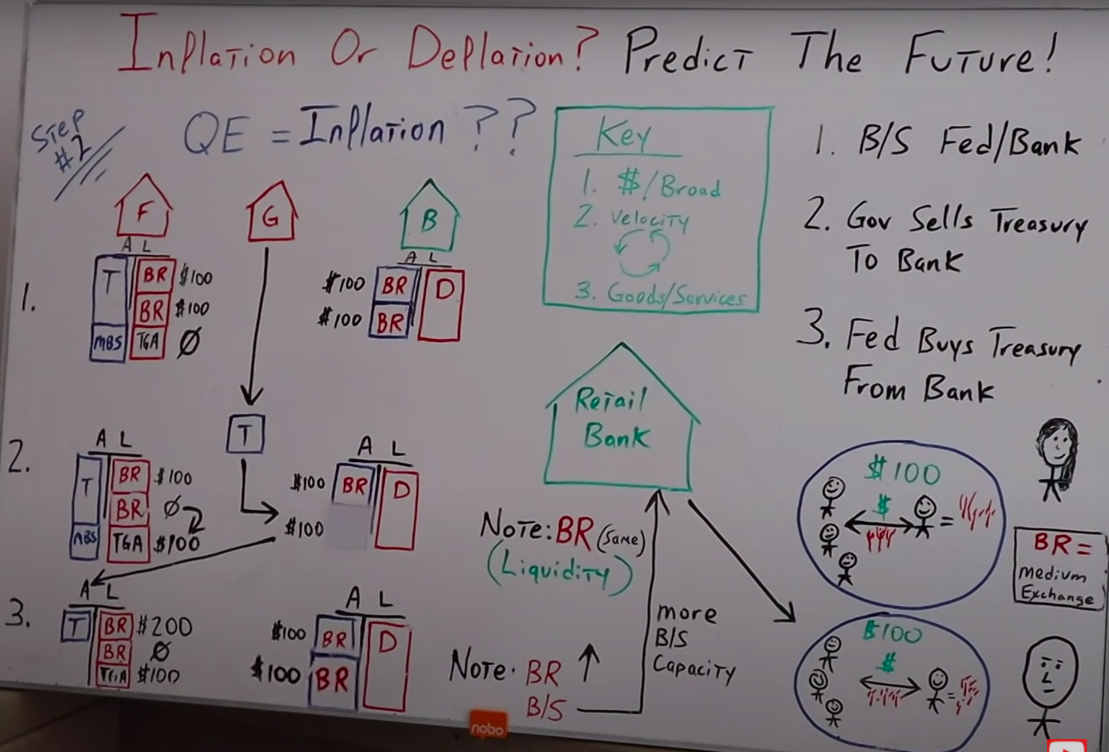

Now, look at the following board and pay attention to the green square, inside, there are some key points that I'm going to reference for the entire article.

Key Factor

- When we're talking about what type of money really affects inflation or deflation, it's really the broad money. This is the money that is circulating in the real economy, chasing goods and services.

- We also need to be concerned with velocity. How fast is the money circulating within the economy, and then how many goods and services do we have?

So now that we understand Brent's view and the bond king's view, we understand these key points and the view that bank reserves can only be used to create additional loans.

Now, look at the Fed's balance sheet and at a typical commercial bank balance sheet, shown on the whiteboard with the little red and greenhouse I drew.

On the left side of the board, you can see the Fed has assets and liabilities. Let's assume right now the assets on their balance sheet are treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, as you can see in the blue rectangles.

On the liability side, they have the bank reserves we were talking about and cash for the bank. The banks store their cash at the Fed.

That would be an asset on the bank's balance sheet and a liability on the Fed's. We'll assume that there's $100 in bank reserves and $100 in cash.

Keep in mind we also have the treasury general account, marked as TGA, which is an account with the Fed, and a liability on their balance sheet.

For this example, we'll also assume that there's $100 in bank reserves, $100 in cash, and $0 in the Treasury general account.

So the government issues a treasury they auction off because they need more money to spend, and the bank comes in and buys a treasury that goes into their balance sheet.

That's a new asset for them and in order to pay for it, they transfer the cash that was on their balance sheet to the TGA. What ends up happening after this transaction is the bank reserves held at the Fed are still $100, but the $100 in cash are moved to the TGA.

Then, on the asset side of the bank, they still have the $100 in bank reserves they started with, but now instead of the cash, they have the treasury that they purchased from the government.

I want to point out exactly what just happened to make sure you are following Brent and Steve's logic.

The money supply in this transaction just went down. They've pulled liquidity out of the system.

Why did this happen?

Because there was $100 to start with in the system, and now there's $0 because the $100 went down into the TGA. It's no longer in the banking system circulating within the economy.

The process of the bank buying the treasury from the government pulled that $100 out of the system.

What happens next?

The Fed buys the treasury from the bank.

How does the balance sheet change then?

With everything that happened in mind, there are now $200 in bank reserves. This is where the Fed “prints money” but they're not really printing money, they're printing bank reserves.

So, to buy the treasuries from the commercial bank, the Fed prints $100 of bank reserves and adds it to their account.

The treasuries then go from the asset side of the bank's balance sheet over to the asset side of the Fed's balance sheet.

So we have $200 in aggregate total in bank reserves, the $100 are still in the TGA and there's zero cash for the banks.

The bank’s balance sheet now has $100 in bank reserves that they had to begin with and they have additional bank reserves the Fed gave them to purchase this treasury.

I want to note, in the example I mentioned, first, the cash went down. Liquidity was pulled out of the system. In the next step, the bank reserves and the balance sheet increased.

I want to note, in the example I mentioned, first, the cash went down. Liquidity was pulled out of the system. In the next step, the bank reserves and the balance sheet increased.

Another way to look at this is the banking system has swapped cash for additional bank reserves.

Remember, Brent and Steve, say the only thing that these bank reserves can be used for is to create additional loans.

So, to increase the amount of money supply circulating in the system by the same amount that it was decreased by the bank buying the treasuries from the government in the first place, the banking system would have to create an additional $100 in loans.

The amount of money in the system went down by $100 and that's why there would need to be that additional $100 in lending just to have a wash.

Of course, ideally, they would want the banks to create more money so the money supply in the real economy would increase, not decrease, or just be at the same level.

Brent and Steve will come in and say” Listen, the banks aren't lending. Sure, they give a loan here and there, but on net balance, people are paying off a lot more loans than new loans are being created”

At the very least there's more liquidity being pulled out of the system through the process of quantitative easing than money being injected back into the system by retail banks creating additional loans for consumers, entrepreneurs, businesses, etcetera.

This is why they say quantitative easing is actually deflationary.

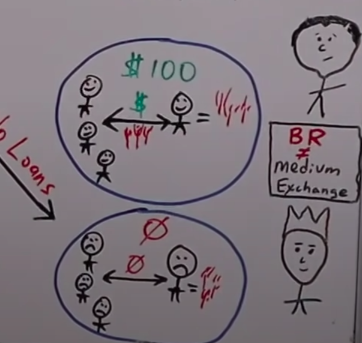

Let's look at it in a very simple way in the economy using my drawing.

We started with $100 circulating. Yes, it was on the bank's balance sheet so probably not real high velocity, but it was in the economy.

We have someone growing wheat inside the circle, and we have three consumers. There is money going back and forth to purchase the wheat, but if that $100 is sucked out of the system, now we have $0.

People don't have any money to buy any wheat and economic activity decreases substantially.

This over-simplified example is why they're both in the deflation camp. They see the dollar getting stronger, and interest rates, potentially going negative.

Lyn Alden And Luke Gromen's Approach: QE Is Actually Inflationary

Two main people on FinTwit hold this view: My partner in crime with Rebel Capitalist Pro, Miss Lyn Alden herself, and Luke Gromen, another good buddy of mine.

The process is pretty much the same, but they think bank reserves are actually a medium of exchange.

This process says the cash on the bank's balance sheet is just a bank reserve that they can use to create more loans or to buy financial assets, which include treasuries the government issues.

That is a massive difference. That's night and day.

Let me walk you guys through why that's such a big deal.

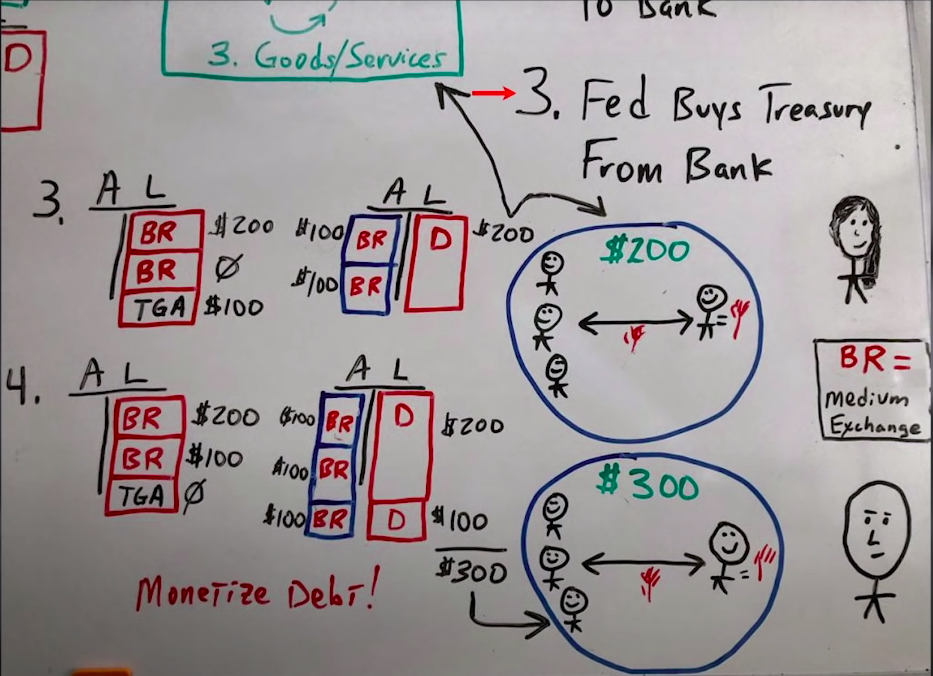

Look at this whiteboard again.

On the left side, you can see the Fed's balance sheet is still the same. It starts with $200 in bank reserves and on the balance sheet of the bank is also the same thing. It has $200 of bank reserves, the liability or customer deposits, and then the assets on the Fed's balance sheets, just the treasury's mortgage-backed securities.

We go through the same process I mentioned before of the government selling the treasury to the bank, so the bank reserves would go from the bank's account down into the TGA. This means there would be $0 on the bank account, $100 on TGA, but there would be no change in the balance sheet of the Fed.

There would be no change to the balance sheet of the asset side of the bank, other than instead of $100 in bank reserves, now they have $100 in bank reserves and $100 in treasuries.

After that, the Fed buys the treasuries from the bank by creating more bank reserves.

Then, the bank reserves on the Fed's balance sheet would now be $200 and the $100 would still be in the TGA.

What changed in the process since my previous example?

Really, it boils down to the question, are bank reserves a medium of exchange?

- If they're not a medium of exchange like Brent and Steve believe, then the liquidity has been sucked out of the system.

Because we started with $100 of cash and that was the only unit of exchange that was on the Fed's balance sheet. We went from $100 down to $0.

2. But as Lynn and Luke believe, if you think that bank reserves are a medium of exchange, then we started with $200 and we finished with $200. The liquidity is the exact same as when we started.

The next question that you're probably asking yourself is, “Okay, George, I get it. The liquidity stayed the same but…

How would quantitative easing be inflationary?

Let's start by looking at a third example.

This time I want to focus on the deposits in the commercial banking system because this is really the money that is circulating in the economy chasing goods and services.

Remember the key to this whole article: It's all about broad money, velocity, and the amount of goods and services.

The Fed's liabilities, regardless of whether they are bank reserves, cash, or how they can be used, aren't as important as the liabilities of the commercial banking system. Because those are the deposits for the everyday person, the people, the businesses, and the entities that are in the real economy.

Looking at example number three, the deposits in the commercial banking system were $200, but remember, the TGA still needs to spend the money. They need to send out those stimulus checks.

Let's say the average Joe that's receiving the stimulus check, banks with the same bank that we've been using in our example.

The TGA would send the $100 to the bank, when Joe deposits the check that he received for $100 in stimulus from the treasury, the bank credits his account $100.

Do you see what has happened?

The deposits in the system have gone from $200 to $300.

Now, the liabilities of the Fed, as far as the TGA, go to $0. But, the reserves, or the cash, whatever it was in the TGA, goes to the bank because it's giving the bank a $100 deposit, therefore, a liability. It also has to give the bank an asset to match up with the liability.

It works the following way:

- The funds go from the TGA to the bank to back up the new deposit that has been created out of thin air for $100.

- The net result is we start with $200 in the system, $200 in commercial bank deposits and we end up with $300.

This is how QE can be inflationary according to Lynn Alden and Luke Gromen because they're saying the Fed is monetizing the debt.

If the economy starts with $200 buying wheat, now it has $300 buying the same amount of wheat, therefore, the price of wheat would most likely increase.

Just so we're clear, let's go over this process one more time.

The TGA sends average Joe a check for $100. The average Joe deposits the check into his bank. Now, the bank has an additional $100 in deposits.

But, the TGA has given the bank an additional $100 of liabilities in the form of the deposits, so they have to back up, they have to transfer an asset to the bank. The $100 of bank reserves go from the TGA to the bank.

The bank now has new deposits or new liabilities of $100, but it also has as a new asset in the form of $100 as well. So, there are now $300 in bank reserves, $0 in the TGA. The asset side of the bank's balance sheet has $300.

Of course, the liability side has $300 as well. We've gone from $200 of commercial bank liabilities to $300 of commercial bank liabilities.

The deposits in the commercial banking system of everyday people and entities, that are out there spending money on goods and services, are the liabilities of the commercial banking system.

That is what really matters the most when we're trying to figure out if the future is inflationary or deflationary.

Those deposits represent the purchasing power that's going to be chasing a certain amount of goods and services.

If the amount of liquidity in the system is the exact same before and after doing quantitative easing, our simple example of an economy starts with $100 and after QE is done, it still has the $100.

There's no deflationary pressure that has been added by quantitative easing.

I want to be crystal clear, I'm not saying one approach is right and the other one is wrong.

The only thing I'm trying to do is explain their positions so you can understand them and make better decisions for yourself moving forward.

You have to realize that what we're playing with here is a hundred-piece jigsaw puzzle where we really only have 10 pieces.

Not just you and I, but also Lynn, Luke, Steve, and Brent, we're trying to figure out what the whole entire picture looks like with just those 10 pieces of the puzzle.

There are 90 pieces actually missing, so there's a lot left to interpretation.

If you want my view and interpretation of what's going on, I encourage you to read my next article on this series.