Negative interest rates distort markets wildly, but most of the time we assume the downside is that they could collapse the dollar or any fiat currency.

But the opposite could also be true. Negative interest rates may cause a dollar hyper-Bubble.

To be clear, the reason I wanted to do this article isn't to argue for or against the dollar becoming a bubble, but it's to introduce outside of the box ideas, so we can all understand the variables involved in macro.

It's never black and white, there is always a shade of grey.

In this article, I will explain:

- How money is created and why it matters.

- The velocity of money and why it matters.

- Negative interest rates effect on velocity and money supply and how it could lead to a dollar hyper-bubble.

How Money Is Created And Destroyed

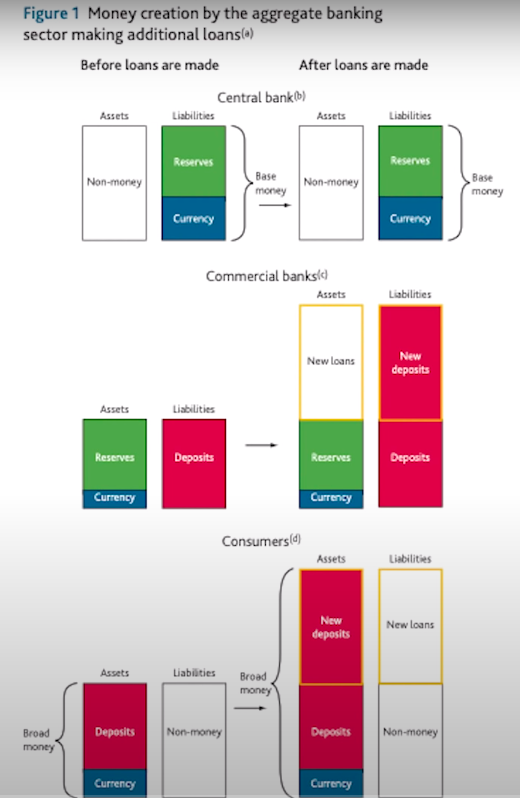

Let's review how money creation works quickly. I'm going to use a chart from the Bank of England's report in 2014, a diagram, just as a reference point.

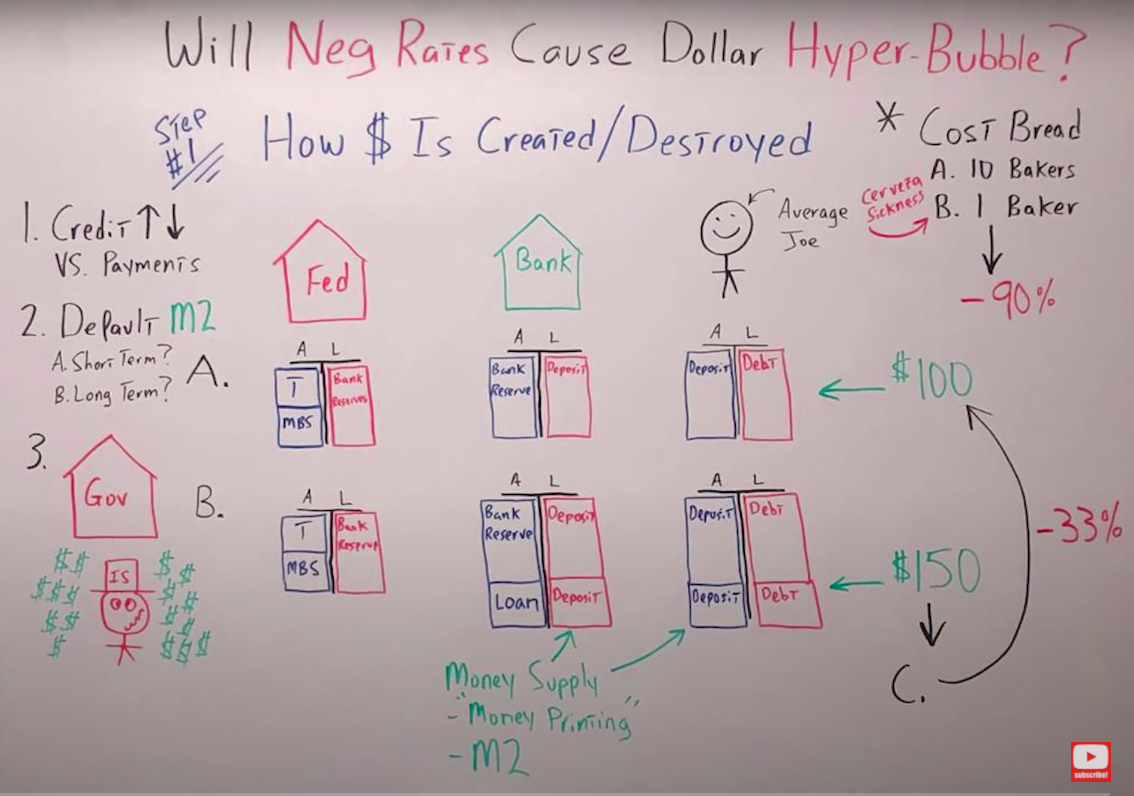

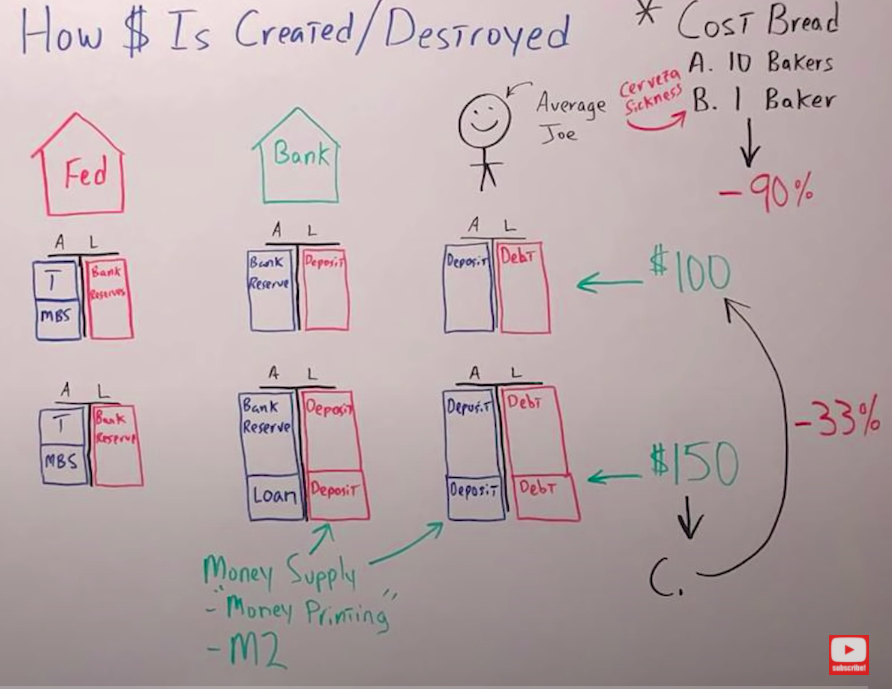

In the following image, you can see I drew three balance sheets.

The central bank on the left, which is the little house that says FED, a normal commercial bank in the middle, and the average Joe on the right.

It starts off with example A. The Fed has treasuries and mortgage-backed sausages, or securities on the asset side of their balance sheet. They have bank reserves, the funny money they create out of thin air.

The commercial banks have bank reserves on their assets, that are the liability of the Fed, and customer deposits.

Finally, on Joe's Balance sheet the deposits are his assets and his liabilities, typically, those are going to be debt, or maybe equity, if he doesn't have much debt.

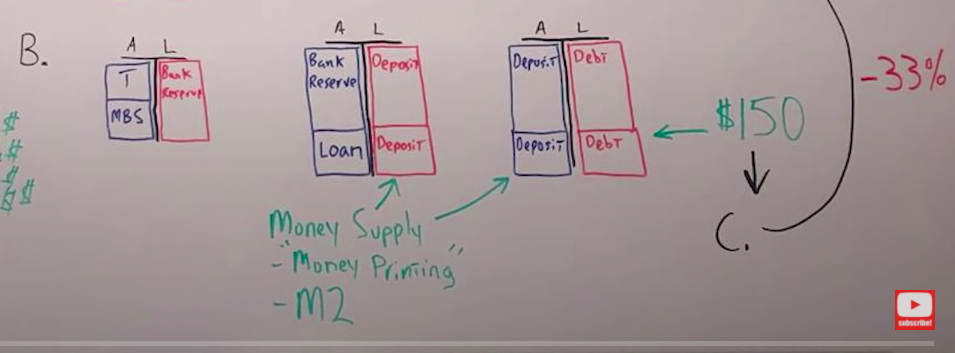

In Step B, let's see how money is created.

The average Joe goes to the bank and says, ” I need to get a loan for a car or a house.” The bank says, “Okay, no problem.” So they create a loan for the average Joe.

This loan becomes an asset on the bank's balance sheet, and they create an additional deposit in Joe's account. In this process, money has been created.

If we started with $100 of money supply, all of a sudden, now that Joe took out this loan, or the bank gave him extended credit to him, we have $150 in the total money supply.

This is considered money printing by people like Dr. Lacy Hunt, someone who's always on MacroVoices and has been on Real Vision, one of my favorites, and it's considered M2, money supply, or broad money, if you're looking at charts from the Federal Reserve.

But in example C, it can go in the opposite direction.

Let's say Joe took out that loan and he immediately paid it back. The money supply would decrease by 33% and go right back to $100.

This is a quick example of how money can be created and destroyed, but let's think through a couple of things before we move on.

First, let's look at what could happen to the cost of bread. When we add $150 in the system, let's say we had 10 bakers.

Now, because of the Covid-19, people are paying down their debt, let's say the money supply contracts down to $100. That's the deflationist argument.

But, because of the supply contraction, due to Covid-19 the number of bakers goes from 10 all the way down to one.

We reduced the supply of bread by 90%, while the money supply is contracting by 33%.

What's most likely going to happen to the price of bread in this situation?

It's going to go up. The objective of this video is not to argue for inflation or deflation. It's just to give you some food for thought.

- First takeaway: As seen on the left side of the board, credit going up or down, versus the amount of principal payments that are being made, is going to give you your broad money supply.

- Second takeaway:

What happens if there's a default?

So people don't pay back the loan at all. Usually, we don't think through this process, but it's very important. Two things can happen

a)Either it can do nothing, because the money is still out in circulation, meaning the money supply doesn't change.

b)Or over time, it could decrease the money supply, if it negatively impacts the bank's balance sheets enough to prevent them from lending more or creating more money in the future.

- The third takeaway is the wild card. The government, your drunk insolvent uncle Sam, has the ability to create deposits or to create money supply by spending it into existence, having the Fed monetize the debt.

If they continue to deficit spend $4, $5, $10 trillion a year, that could create additional money supply above and beyond what's being destroyed by principal payments, or banks not lending as much as they were in the past.

The biggest takeaway from the question ” How is money created and destroyed is, you realize commercial banks have the most control over the money supply.

They can expand the money supply by lending it into existence at a faster rate than people are paying down the principal.

The money supply, on net balance, will expand. Or, if they don't lend at a fast enough rate to keep pace with the amount of principal that's being paid off on net balance, the money supply will decrease.

Figuring Out If Negative Interest Rates Can Create A Dollar Hyper Bubble

We discussed why the money supply goes up and down, but now, we really need to understand velocity. It's just as important as the money supply going up or down when we're trying to figure out if negative interest rates can create a dollar hyper bubble.

We're going to put all the pieces of the puzzle together.

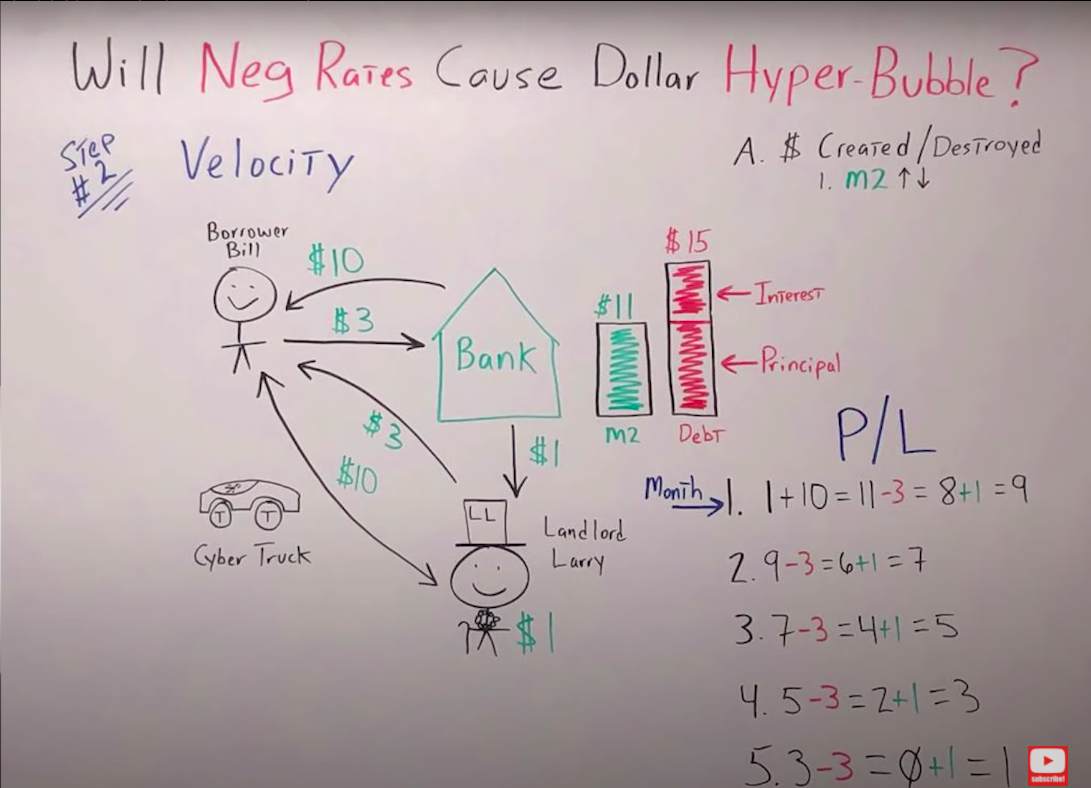

Going back to velocity, here is a scenario where there is $15 worth of debt that we could pay off with only $11 in the system.

It starts off with Landlord Larry, the man with the big hat. He is definitely balling, has his pimp cane and gold chain there. He has a $1 bill in his pocket.

Borrower Bill, the other man on the left wants a job. He wants to be Landlord Larry's chauffeur.

He needs to go to the bank and borrow $10 because Landlord Larry is going to sell him his cyber truck for 10 dollars, so Bill can drive Larry around and make some money.

Bill goes to the bank and says, “Listen, I need a loan for 10 dollars.” The bank says, “Fine. Here you go.” The bank gives him the $10.

Borrower Bill gives the $10 to Landlord Larry and Landlord Larry sells him his cyber truck.

Now there are $15 worth of debt in the system, $10 of principal, and $5 in interest, but our total money supply or the amount of currency units we have in the system is $11.

Let's assume Landlord Larry is paying Borrower Bill $3 a month to drive him around. With those $3, Bill pays the bank back $2 in principal and $1 of interest, but the bank is leasing space from Landlord Larry.

Of course, they pay him $1 a month in rent. So let's look to see what happens to Landlord Larry's profit and loss.

-

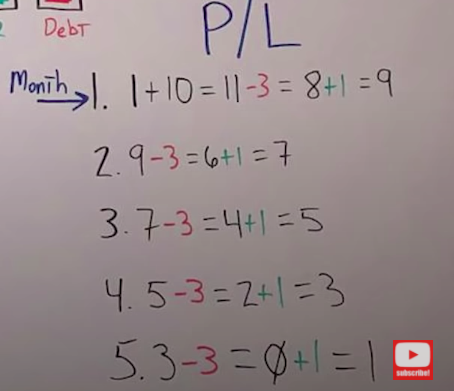

Month one

He starts off with a $1 bill in his pocket. He gets $10 from Borrower Bill, so he has $11 total, but he has to pay Borrower Bill $3. So he has 8$, gets $1 in rent, $9 total.

-

Month two

He has to pay Borrower Bill $3 again, but he gets the $1 in rent. You can see how this plays out. Month two, Landlord Larry has $7 at the end of the month.

Month three he has at the end of the month$5.

Month four, $3 at the end of the month.

Month five, $1 again in his back pocket at the end of the month.

What's happened during these five months is that Borrower Bill has made $15. The bank has been completely paid off, with only $11 in the system.

We can see how important it is for money to circulate within the system. There has to be this velocity, in order for the debt to be paid off.

If it's not, if there's a default, yes, short term, it might not reduce the money supply, but long term, it most likely will.

It'll impair the balance sheet of the bank, and they won't be able to create as much money, moving forward into the future.

The main points I want to emphasize aside from the wild card of government spending are…..

If banks are creating fewer loans, they're creating less money supply, while at the same time, consumers are paying down debt at a faster rate, and you have the velocity of money slowing down, you're going to have fewer and fewer dollars in the system.

Negative Interest Rates Over The Long Term Will Lead To Less Lending And Lower Velocity

Here's how negative interest rates could create the dollar hyper-bubble.

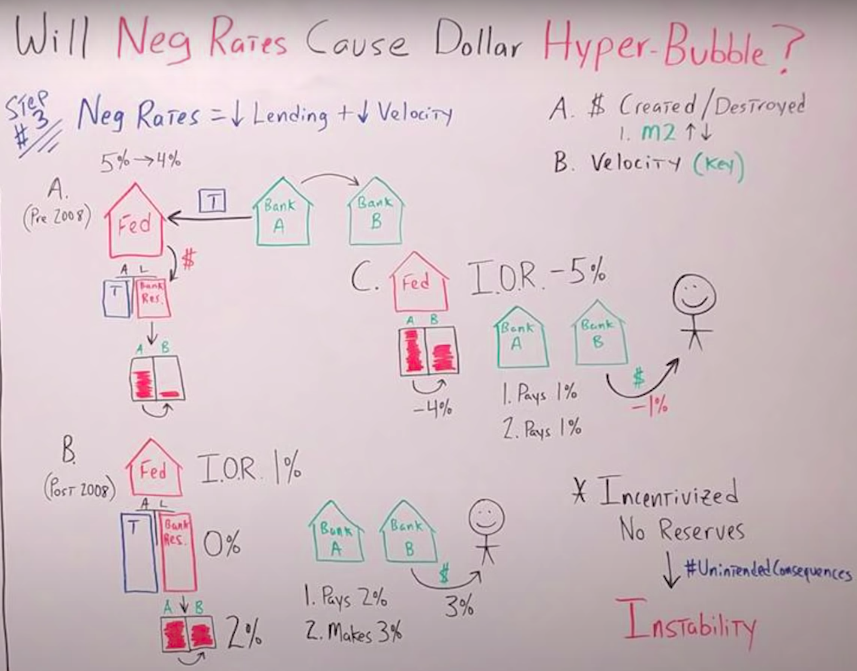

Scenario A starts going back prior to 2008 and understanding how the Fed manipulated the fed funds' interest rate.

I know Jeff Snider would disagree with this. He doesn't think this is how it worked in practice, but here's how they taught it in textbooks.

If the Fed wanted to take interest rates, the fed funds from 5% down to 4%, they would buy Treasuries, or T-bills, from the banking system, the primary dealers.

This would create more liquidity in the system, or more cash, because what happens?

The Fed buys the T-bill from, let's say, Bank A, and they print up funny money and put it in Bank A's reserve account with the Fed.

This creates more bank reserves in the system. Therefore, if Bank B needs to borrow money from Bank A overnight, there's more money in the system.

Therefore, interest rates for overnight lending most likely go down. Just simple supply and demand.

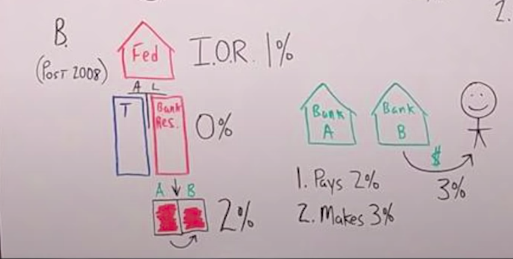

Now, look at scenario B.

In 2008-2009, the Fed started quantitative easing.

This injected so much funny money and bank reserves into the system, the interest rates dropped straight down to zero, and there's no way the Fed could have increased interest rates, because there was just too much cash in the system.

The overnight rate would have been at zero, or possibly at negative, but most likely it would have just been stuck right at zero.

The Fed introduced something called IOR and IOER. This is Interest on Reserves or Interest on Excess Reserves. If the Fed wanted the interest rates, the fed funds at 1%, they would pay banks 1% on their reserves.

Now, what would happen, if Bank B needed to borrow money from Bank A, Bank A would charge Bank B a higher rate of interest than 1%.

Because why would they lend any money at all, when they could just get 1%, with their bank reserves parked at the Fed.

What happens with Bank B? Let's say they need to make a loan. I want to be clear, they're not lending their bank reserves. They're just using those bank reserves to backstop the loans they're creating.

That goes back to how money is created, but remember. They're not lending their bank reserves, they're just using their bank reserves to back up the additional loans they're creating.

I want to be redundant on that because it's very difficult for people to understand that concept.

So, in scenario B Bank B would make a loan to the customer at 3%.

The customer is paying bank B the 3%, but Bank B would pay 2% for the reserves that back up the loan.

They're pocketing the 1%. But look at example C

What would happen if the Fed takes IOR negative, let's say, at a negative 5%? If Bank B needed to borrow money again, Bank A would lend them the money, and they'd pay them to take the money.

Why on earth would they do that?

Because the Fed is charging them 5%. If they can pay someone 4% to take their money, they're making 1% on the transaction and this is where most people get really confused.

They say, “Bank B is being paid 4% to borrow the money, even if they lend it out and have to pay the borrower 1%, Bank B is still making money.

Because they're pocketing the spread between the negative 4% they're being paid, and the 1% they're having to pay the customer, to borrow the money.”

But let's think through what happens to the money Bank A pays Bank B 4% to borrow, those are reserves.

Bank B takes the money, and puts it in their reserve account, in which the Fed charges them 5%. This is a scenario where although Bank B is being paid 4% for the money, they're being charged 5% to hold it at the Fed.

They have to pay 1% when everything nets out for the reserves and they have to pay the borrower 1% for taking the money that they create through the loan.

Any way you slice it, that is a horrible business model.

What it boils down to is, even if the banks were able to charge the customers for their deposits, because the system has been so distorted, there'd be a lot less lending moving forward.

A lot less lending means a lot less money supply, which equals fewer dollars.

Let's not forget the massive unintended consequences the Fed creates if they were to take interest rates into negative territory for a long period of time.

Of course, this incentivizes the banks to have no reserves whatsoever.

Think about it, If you were a bank that was being charged 5% for your reserves, you'd want as little reserves as possible. But if they have no reserves, what does that do to the entire banking system? It makes it far more unstable.

While the banking system in the domestic economy is becoming far more unstable, producing fewer dollars, and velocity is decreasing.

Outside of the United States, there are $13 trillion-plus dollars in debt from corporations and governments and there aren't enough dollars to pay the debt, because velocity has been decreasing at such a fast pace.

We also have the attitude within the United States, that there is going to be a lot less trade.

Why do I say that?

Because the narrative that you hear constantly right now is, “No more China, bring jobs back to the United States, and we don't want to rely on imports any more.”

If there are fewer imports, that means there are a lot fewer dollars being exported. If you have fewer dollars being created, fewer dollars getting into the global economy, it makes the 13-plus trillion harder to pay.

What ends up happening is, XYZ CEO and ABC CEO on the whiteboard, that have dollar-denominated debt, but don't have any dollars because they use their local currency, go into the FX market, and bid up those dollars.

Let's say there is $100 in the market. They'll pay $110 pesos. They'll say, “No, I'll pay 120.” The next guy says, “I'll pay 130 of my currency units for those dollars.”

You see what happens to the dollar relative to all the other currencies, is it goes up and up.

Now, a lot of people would argue, “George, but they've come out the swap lines, where the Fed is extending lines of credit in dollars to other central banks, so that will take care of the issue.”

But if we listen to Jeff Snider, we know that isn't necessarily true. Here is part of his show, Making Sense, Eurodollar University.

Interviewer: The question is, does unlimited dollar funding to other central banks solve this issue? The issue is offshore dollars, dollar swaps, the Federal Reserve.

Jeff Snider: No, it doesn't. The reason is that, again, we have to break it down and then understand exactly what the Federal Reserve is doing.

What the Fed is doing is offering dollar swaps to other central banks around the world.

Initially, it was only a group of five central banks, the major central banks around the world.

No China, no emerging markets, none of those people were involved, until later. It wasn't until March 18th and 19th that the Fed finally changed its rules.

What the Fed is doing, in the figurative sense, is it is not performing its role of dollar central bank. It's saying, “Look, dollar problems outside of the United States, aren't really our problem.

But we recognize there is an offshore dollar system, therefore, we have to do something, so we're going to do as little as we possibly can. That little we possibly can is to let other central banks sort out their own dollar mess.”

The Fed is giving these dollar swap lines to other central banks so that these other central banks around the world try to handle a dollar shortage in their own local jurisdictions.

Of course, central banks are not set up to redistribute dollar resources in an efficient and dynamic manner. They're very bureaucratic, and they're rigid.

(End of transcript)

If the central banks really don't have an efficient transfer mechanism to get the dollars into the system, down through the banks and to the corporations, you go through this bidding process, where the dollar just keeps going up.

The central banks and the Fed don't have a way to combat it and if the system stays the same as it is today, that is key.

And, we introduce negative interest rates, you can see how the dollar could go into a hyper-bubble.

I'm talking about the DXY going from 100 to 120, to 140, as you can see in the following chart. Who knows where it could end?

To answer the specific question:

Will negative interest rates create a dollar hyper-bubble?

It all depends on the Fed and the government's ability to bend and/or break enough rules, to create the additional M2 money supply, without the commercial banks.

If they can't create the money supply without the banks, we very well could see a dollar hyper-bubble.

In fact, I would say it's most probable. But if they're able to figure out a way to create additional money supply and then they take it to an extreme, which we know they most likely will because the government has to inflate away their debt, we could see the complete opposite.

Where instead of a dollar hyper-bubble, the dollar completely collapses.